SECTION 02

The End of World War One

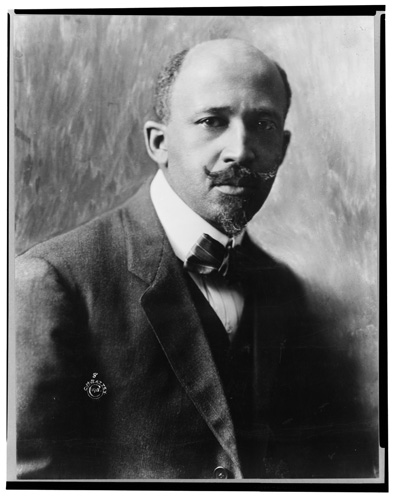

W.E.B. (William Edward Burghardt) Du Bois, 1868-1963.

Source: Cornelius M. Battery, May 31, 1919, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

When the United States entered World War I, many African Americans hoped that the international conflict might create greater opportunities for eliminating racial discrimination. Blacks purchased more than $250 million worth of war bonds and stamps to assist the country’s war effort. Nearly 2.3 million registered for the draft, and 367,000 were enrolled in the armed forces. Many believed that their service in the war would prove to the government the injustices of racial segregation and inequality. If one was willing to fight and die for one’s country, shouldn’t the powers of that country do all in its ability to protect those men and women at home? Yet, the Wilson administration, reluctant to send large numbers of African American troops to France, feared that the support of black troops would undermine the domestic policy of strict segregation. In the end, forty thousand black troops in the 92nd and 93rd divisions were deployed to Europe during the war, but assigned to fight with the French to maintain the segregation of American troops.

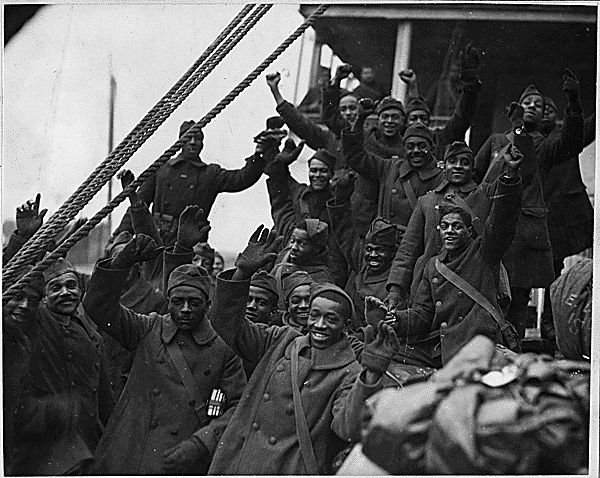

New York's famous 369th regiment arrives home from France, 1919.

Source: ca. 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

One of these regiments was the 369th. Nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters, they were the first all-black regiment to fight in World War I. Even before they left for duty, the Hellfighters had to endure the racist taunts, jeers and violent attacks of their fellow white soldiers on the Camp Whitman base. The regiment had arrived in France in early 1918 and was trained for several months in French military camps. By May they were fighting on the Front lines, where they spent the next six months-- longer than any other American unit during the war. The entire unit was given the distinguished Croix de Guerre by the French national government for their service.

Yet, despite the sacrifices and courage displayed by African American soldiers during the war, they nevertheless encountered a virulent backlash of white racism upon their return to the United States. A number of newly discharged soldiers- still wearing their uniforms- were lynched by white mobs. The post-war landscape was rife with racial and economic tension. The demobilization of the troops was met with severe and rising inflation and unemployment. At the war’s end, approximately 9 million people were employed in industries pertaining to the overseas effort. The war effort had provided openings for the migration of blacks into urban manufacturing jobs, but with the war’s end job scarcity fueled the notion among working class white workers that blacks were taking their places in the labor force.

Racial violence erupted in the summer of 1919, in what Harlem Renaissance poet and intellectual James Weldon Johnson would call “Red Summer.” On 27 July, in the Northern city of Chicago, Eugene Williams was drowned by white swimmers who threw rocks at the young African American boy for swimming too close to a white beach. The black community was outraged after police refused to arrest those responsible for Williams’ death. Rioting erupted throughout the city, and for the next five days, black neighborhoods were the sites of terror, burning and lynching. By the beginning of August, the city lay in disrepair, 38 dead, 500 injured, and over 1,000 black people homeless.

The fear of organized black labor was the catalyst for more racial violence and terror in Elaine, Arkansas. In early October, as black farmers and sharecroppers met to organize a union, a white mob swarmed down upon them in attempts to break up the meeting. The violence that ensued left over 100 black farmers dead and their farms destroyed. Throughout the South, independent black farmers and unions became the targets of racist violence and lynching.

Throughout the summer and fall, 24 other race riots erupted within American cities, all instigated by white acts of violence. In the Washington, D.C. riots, whites were shocked to find that black urbanites quickly organized collective resistance and militantly stood their ground. Indeed the war had meant something to black Americans; it meant that if they were to support the fight for democracy abroad, they would wage one for equality at home.

Related Resources

W.E.B. (William Edward Burghardt) Du Bois, 1868-1963.

Photograph of W.E.B. Du Bois, taken May 13, 1919. After calling upon African Americans to "close ranks" with the rest of the country during World War I, he declared to America, "Make Way for Democracy!" in 1919, as returning soldiers along with other blacks continued to suffer racial discrimination and attacks.

Source: Cornelius M. Battery, May 31, 1919, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Lt. James Reese Europe.

Lt. James Reese Europe, who for four years was New York Society's favorite orchestra leader, served as regimental jazz band leader of the 369th Infantry, nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters. During their victory parade down Fifth Avenue in New York in 1919, the soldiers marched to the music of his band.

Source: 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

New York's famous 369th regiment arrives home from France, 1919.

Nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters, the 369th Regiment was the first all-black regiment to fight in World War I.

They arrived in France in 1918 and fought on the front lines for six months, longer than any other American unit during the war.

Source: ca. 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

369th Regiment homecoming parade.

Children gathered along parade route celebrating the return of the 369th Regiment to New York, 1919.

Upon their return from France, the members of the 369th Regiment were honored as heroes with a parade down Fifth Avenue in New York in 1919.

Source: ca. 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.