SECTION 05

Early Labor Movement

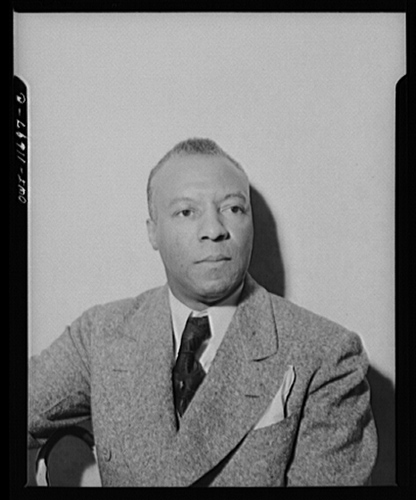

A. Philip Randolph, ca. 1935-1945.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

To Garvey’s left, a generation of black radicals also challenged the middle-class-oriented leadership of the NAACP. Black labor leader and socialist A. Philip Randolph established in 1935 the short-lived National Negro Congress, a coalition of over seven hundred black groups, advocating civil rights and economic justice. An avid proponent of organized labor, Randolph was responsible for advocating the primacy of unions for black workers. While the American Federation of Labor (AFL) did not exclude black members in their manifesto, African American laborers were de facto excluded from positions of influence if they were allowed to join at all. Because labor remained segregated throughout the nation, black workers were generally given the dirtiest, most grueling jobs on the shop floor with the least compensation.

Skilled jobs such as railroad engineers, steamfitters, electricians, machinists, cranemen, plumbers and pipefitters, and many other occupations were designated for whites only. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters started in Harlem in 1925, and was led by Randolph and Chicago porter organizer Milton Webster, as a response to the Pullman Car Company’s discriminatory disregard for their black employees’ needs. After twelve years of difficult struggle and fierce resistance, Pullman finally agreed to negotiate a contract with the BSCP in 1937. This success was central in underscoring the importance of unions for African Americans, who have historically been significantly more supportive of unionization than white Americans.

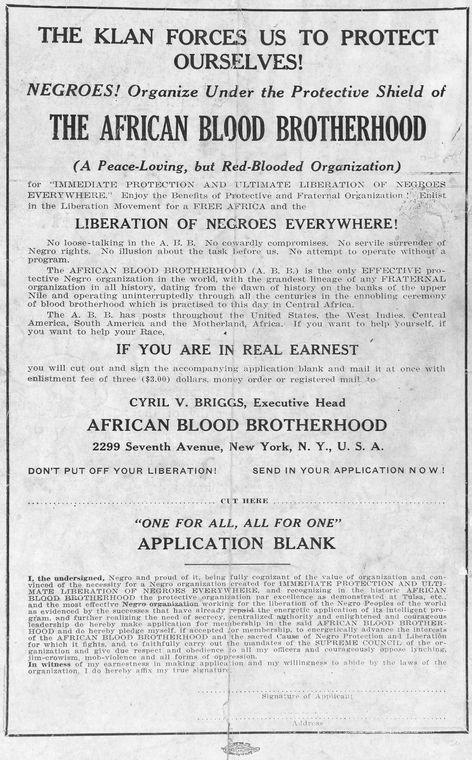

African Blood Brotherhood membership application.

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture / Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division.

With the growth of the black urban working class, increasing numbers of African Americans joined the ranks of organized labor and left-wing political organizations. West Indian immigrant Cyril V. Briggs started the African Blood Brotherhood in 1921, a radical black formation dedicated to “the immediate protection and ultimate liberation of Negroes everywhere.” Staunchly anti-capitalist and anti-colonialist, the ABB launched the radical news journal The Crusader to push the organization of the black working class. Although their membership was never as large as that of the UNIA, their radical ideas remained salient to leaders searching for radical ways of pushing for a more equal society.

As early as the 1920s, the Communist Party attracted significant numbers of African-American political organizers and labor activists, including the militant independent group the African Blood Brotherhood and writers like Richard Wright. After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the American Communist Party grew in the 1920s and gained support among thousands of black workers and rural farmers. In the midst of the Great Depression, the Communist Party under the Third International declared the Alabama Black Belt an oppressed nation with rights to their own political and economic control, echoing the cries of Garvey and Briggs for black determined communities. This resolution shaped the Party’s entre into the South, and more importantly, the ways in which communism emerged within an ideological perspective of Black self-determination. Black Communists organized massive rent strikes and unemployment councils in the economically depressed communities of Harlem, Chicago’s South Side, and in other cities. In the early 1930s black Communists established the Sharecroppers’ Union in the Black Belt South, assisting tenant farmers and farm laborers in demanding decent wages and better working conditions.

Related Resources

African Blood Brotherhood membership application.

The African Blood Brotherhood advertisement and membership application, published in the The Crusader, 1918-1922.

Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture / Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division.