SECTION 01

Jim Crow

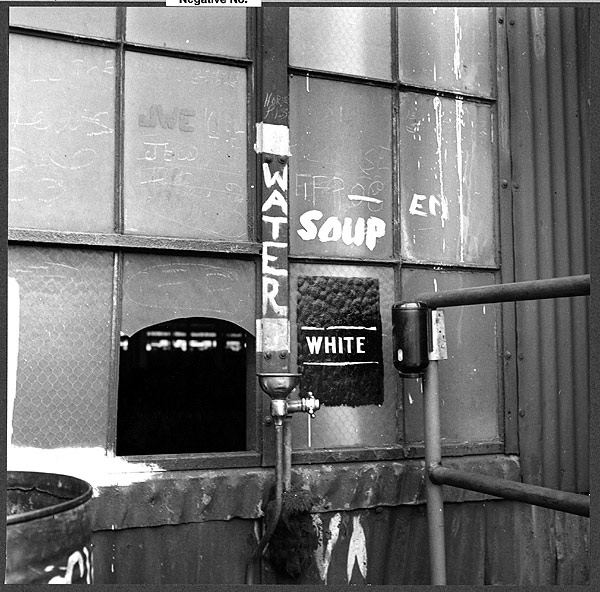

Water fountain for whites, Baltimore, Maryland, 1943.

Source: Arthur Siegel, May 1943, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

The end of Reconstruction produced a political and social climate of fear and intimidation for every black person in the South. Despite a brief period from the late 1880s to the mid-1890s when black and white southern farmers attempted to develop a biracial opposition to the planters through the Populist Party, the conditions of black life and labor deteriorated rapidly. Politically, the federal government abandoned any commitment to biracial democracy. In 1883, the Supreme Court declared the Civil Rights Act of 1876 unconstitutional. The principle of “separate but equal,” America’s legal justification for domestic apartheid , was ordained by the Supreme Court in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. Systematically, the gains made towards a more equal society during Reconstruction were dismantled and replaced by a new system of injustice. The Jim Crow system of racial exploitation was, like slavery, both a caste/social order for regimenting cultural and political relations, and an economic structure that facilitated the super-exploitation of blacks’ labor power. The exploitation of slave labor was replaced with share-cropping: a system by which former plantation owners leased land at exorbitant prices to former slaves, and then over-charged them on everything, thus creating a system of debt peonage.

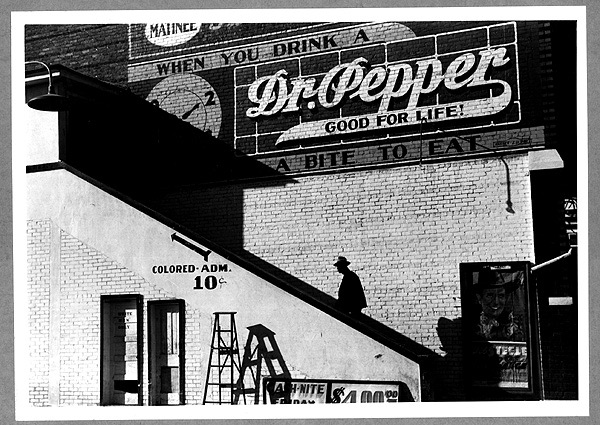

Negro man entering movie theater by "Colored entrance," Belzoni, Mississippi, 1939.

Source: Marion Post Wolcott, October 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Furthermore, Jim Crow laws meant the institutional segregation of all public and private facilities and access to employment and housing opportunities and resources. Under the notion of separate but equal, segregation became a legalized institution so long as alternatives were provided for black people’s use. However, though facilities, schools, entrances to public transportation, housing, and social spaces remained separate, they were never of equal quality. In this system, access and quality were always substandard for people of color.

There was little in the way of political rights to protect black Americans from economic exploitation. By the 1880s, Southern states had begun to rewrite their Reconstruction-era constitutions, denying blacks and many poor whites the right to vote. The effect of these new state constitutions was as striking as it was undemocratic. In Alabama, for example, there were 181,000 blacks who were eligible to vote in 1900; two years later, merely 3,000 were noted as registered voters. Republican presidents supported the creation of a “Lily White” wing of their party in the South, which would deny blacks the right to participate even in their own political organizations.

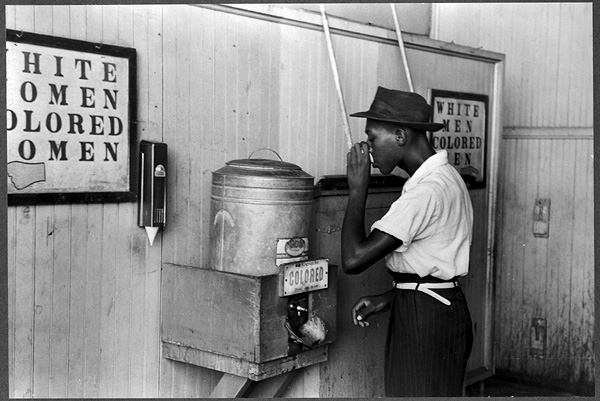

Man drinking at a water cooler reserved for "Colored," Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 1939.

Source: Russell Lee, July 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

This system was dependent upon the omnipresence of violence or coercion. Throughout the early twentieth century, white politicians, business leaders and most workers defended the necessity to discipline the black working class via lynching, public executions, and the like. Political disfranchisement was also facilitated by extra-legal means. Between 1882 and 1903, 2,060 blacks were lynched in the United States. Some of the black victims were children and pregnant women; many were burned alive at the stake; others were castrated with axes or knives, blinded with hot pokers, or decapitated.

Related Resources

Water fountain for whites, Baltimore, Maryland, 1943.

Throughout the South, separate public facilities and accommodations were commonplace, such as this water fountain marked for whites in a Baltimore, Maryland shipyard in 1943.

Source: Arthur Siegel, May 1943, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

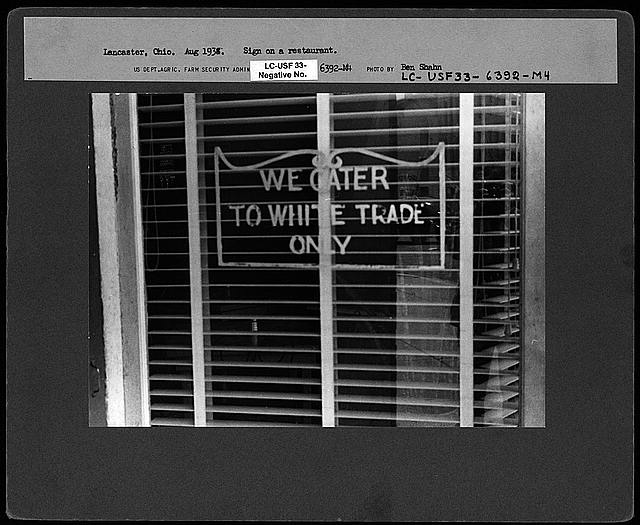

Sign on restaurant indicating "We Cater to White Trade Only," Lancaster, Ohio, 1938.

During Jim Crow segregation, some business establishments did not service black patrons at all. This sign on a restaurant in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1938, is clear about serving whites only.

Source: Ben Shahn, August 1938, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Man drinking at a water cooler reserved for "Colored," Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 1939.

Separate water fountains for blacks and whites, providing such basic a human need as water, highlighted how far-reaching racial discrimination was during the Jim Crow era.

Source: Russell Lee, July 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

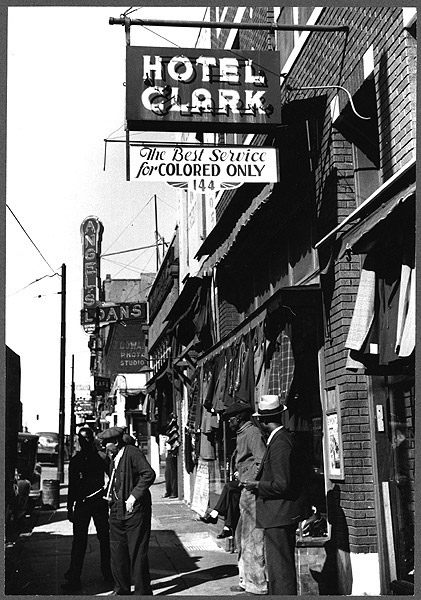

Hotel for "Colored" patrons, Memphis, Tennessee, 1939.

Barred from the same hotels available to whites, African Americans relied on hotels such as the Hotel Clark on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee to provide accommodations.

Source: Marion Post Wolcott, October 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

"White Ladies Only" restroom at bus station, Durham, North Carolina, 1940.

The "White Ladies Only" sign on the restroom at this bus station in Durham, North Carolina, in 1940, was typical of Jim Crow segregation of public bathrooms throughout much of the South.

Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

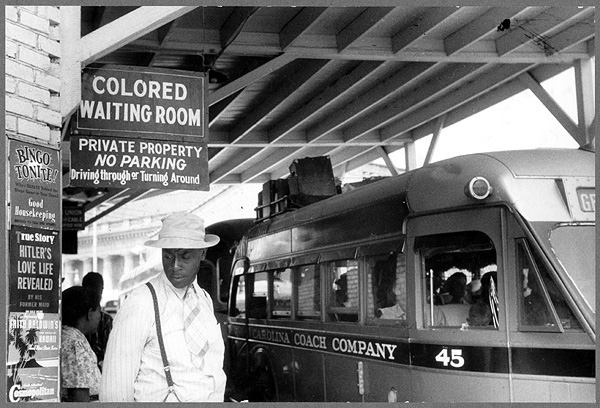

"Colored Waiting Room" at bus station, Durham, North Carolina, 1941.

African American travelers throughout the South were directed to "colored only" waiting areas at bus stations, such as this one in Durham, North Carolina, in 1940.

Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

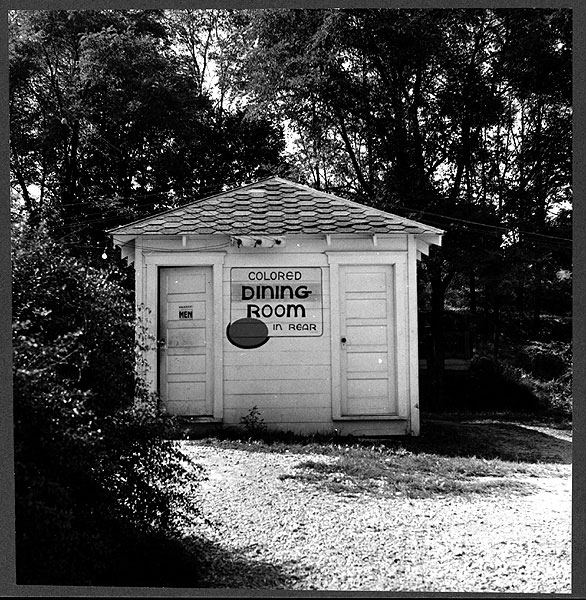

"Colored Dining Room in Rear."

A rest stop for Greyhound bus passengers on the way from Louisville, Kentucky to Nashville, Tennessee, with separate accommodations for colored passengers.

When patronizing restaurants and diners that also catered to whites, African Americans usually entered through separate entrances (often through the kitchen or through a rear entrance), and ate in separate areas.

Source: Esther Bubley, September 1943, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

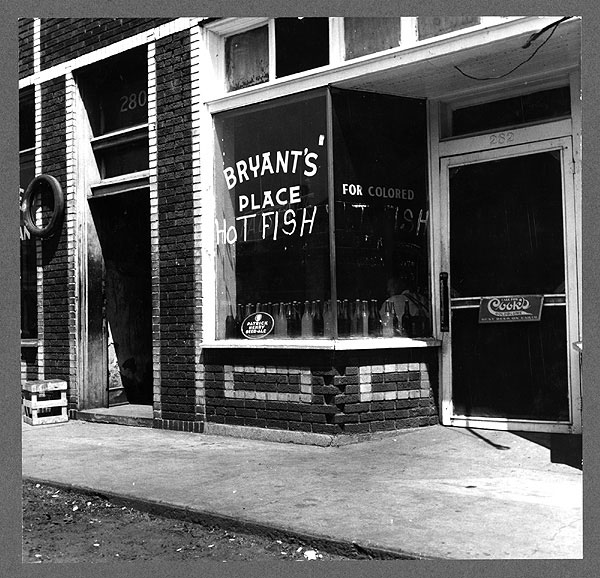

A fish restaurant for Negroes, Memphis, Tennessee, 1937.

Subjected to second-class treatment at restaurants and diners that also catered to whites, many African Americans chose instead to patronize business establishments that catered specifically to blacks, such as this fish restaurant in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1937.

Source: Dorothea Lange, June 1937, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

A cafe in the warehouse district with separate doors for "White" and "Colored".

A cafe in Durham, North Carolina with separate entrances for "White" and "Colored," in 1940, typical of eating establishments throughout the South during the Jim Crow era.

Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

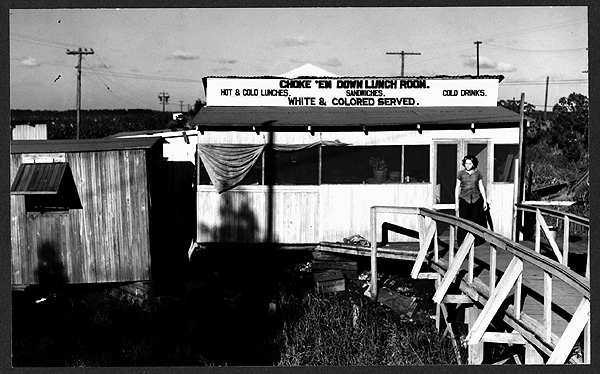

A lunch room for "White & Colored," Belle Glade, Florida, 1939.

This lunch room in Florida in 1939, assures service for both "White" and "Colored" at a time when many establishments refused service to African Americans.

Source: Marion Post Wolcott, January 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Negro man entering movie theater by "Colored entrance," Belzoni, Mississippi, 1939.

Black movie goers were directed to separate seating areas, usually in the balconies, of theaters, such as this one in Mississippi, in 1939.

Source: Marion Post Wolcott, October 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.