SECTION 10

End of World War Two

United We Win [World War II Poster] (1943)

Source: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Many believe that the watershed of African-American history occurred during the 1940s. Thousands of black men working as sharecroppers and farm laborers were drafted into the army with the outbreak of World War II. Over three million black men registered for the service, and about 500,000 were stationed in Africa, the Pacific, and in Europe. Fighting, as was customary, in segregated units, black troops again distinguished themselves on every front. At home, the war effort brought another million black women and men into factory lines of production. Some white workers viewed this racial turn of events with greater alarm than the specter of fascism.

Between March and June 1943, a series of “hate strikes” against the upgrading of blacks in industries contributed to a total of 100,000 man-days lost. Philadelphia streetcar workers refused to work with blacks in 1944, and Roosevelt was forced to order 5,000 federal troops into the city to restore order. Thus for many African-Americans who celebrated V-J Day in the late summer of 1945, there was both a sense of joy and dread: fears that there might be another anti-black “Red Summer” such as had swept the nation in 1919; a continuation of the riots of 1943; hopes that the progressive economic changes that had occurred for blacks during the wartime era could be expanded; and unanswered questions about the new administration of Harry S. Truman, its commitment to the modest social democratic policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and to the limited pursuit of civil rights.

Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. and Edward Gleed of the Tuskegee Airmen, March 1945.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

In the months immediately following World War II, blacks made decisive cracks in the citadel of white supremacy. Across the country, blacks were participating openly in electoral politics in heretofore unprecedented numbers. During the 1940s, there was also a marked improvement in the quality and accessibility of black education. In the 1930s, the incomes of private black colleges had decreased by 16 percent, and private gifts declined by 50 percent. In October 1943, a group of black college presidents, led by Tuskegee Institute president Frederick D. Patterson, established the United Negro College Fund to save these institutions. By 1950, 83,000 black women and men between the ages of 18 to 24 were enrolled in universities, 4.5 percent of their age group. In the labor force, a similar picture of change emerged. The median income of employed black workers rose from 41 to 60 percent of the median white income in the ten years before 1950. The number of employed white collar professionals was improving as well.

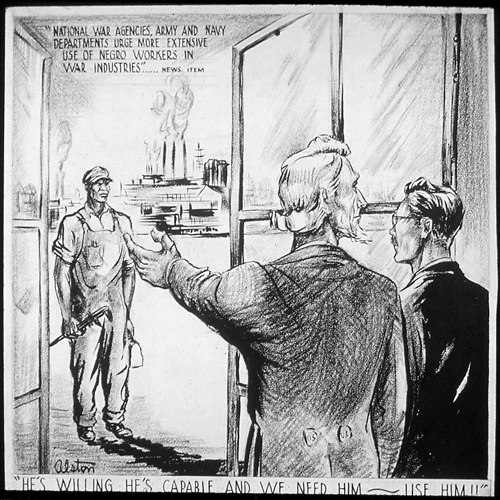

"He's Willing, He's Capable, and We Need Him - Use Him!" (1943).

Source: Office of War Information, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Yet, with the onset of the Cold War, the gains made throughout labor, voting and education began to seem like little more than lip service to the American Dream. By the spring of 1954, nine years after Roosevelt’s death, there was a feeling of unfulfilled ambitions and expectations among many blacks. The gains made did not benefit everybody. The legalistic strategy of the NAACP had proved successful, yet desegregation efforts were slow, and rarely affected the everyday lives of factory workers, domestics, or the returning GIs. During the last five years of Truman’s administration, non-white unemployment averaged 6.9 percent, compared to 4 percent for white workers. By 1954 and 1955, non-white unemployment had jumped to 9.3 percent versus 4.5 percent for whites. In 1954, 16.5 percent of all non-white youths in the job market were unemployed. The black neighborhoods of the North, first taking shape with the industrial demand for Negro labor a half century before, were beginning to become stagnant centers for joblessness and despair.

The first four decades of the twentieth century witnessed major social, cultural and economic changes for most black Americans. Yet after two world wars and a devastating economic depression, the barrier of the color line still existed in the United States. Most white Americans, looking backward at Reconstruction, cautioned black leaders not to demand abrupt changes in their caste status too quickly. Jim Crow would gradually be allowed to decline after another century or two of racial improvement and social adjustment. But in growing numbers, blacks and other national minorities looked at America’s experiment in multicultural democracy as the harbinger for a better life in the immediate future.

Republican Dwight David Eisenhower had been elected president in 1952. No friend of the armed forces desegregation decision of 1948, the former five-star general wanted to slow down the pace and retard the movement for civil rights. Dewey’s vice presidential running mate of 1948, California governor Earl Warren, had been named chief justice of the Supreme Court. For blacks, he was best known for placing 100,000 Japanese-Americans into concentration centers during World War II. Neither Eisenhower, the NAACP, nor black America knew that this same Republican politician would become the strongest defender of blacks’ rights in Supreme Court history. No one could realize completely the new phase of American history that would dawn on 17 May 1954, in a legal decision which would mark the real beginning of the Second Reconstruction.

Related Resources

United We Win [World War II Poster] (1943)

In an effort to counter the demoralizing effect of racial segregation and discrimination, the U.S. government launched several campaigns that highlighted the contributions of African Americans to the war effort.

Source: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

"He's Willing, He's Capable, and We Need Him - Use Him!" (1943).

This cartoon encourages defense industry employers to hire African American workers.

Source: Office of War Information, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

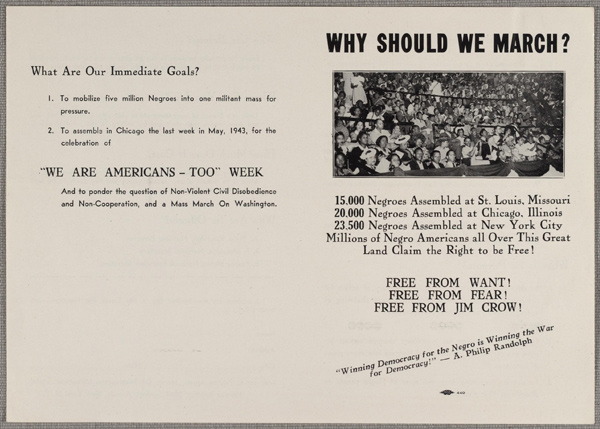

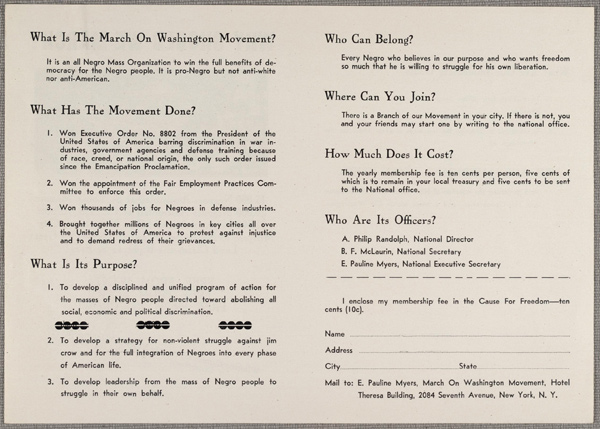

Flyer for March on Washington Movement, 1941 (Slide 1).

In 1941, civil rights activist and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in defense industries.

Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C.

Flyer for March on Washington Movement, 1941 (Slide 2).

In 1941, civil rights activist and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in defense industries.

Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C.

Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. and Edward Gleed of the Tuskegee Airmen, March 1945.

During World War II, in response to civil rights activists call for equal treatment of black soldiers, the government provided training for black pilots in a segregated base located in Tuskegee, Alabama. The 99th Pursuit Squadron, an all-black fighter unit known as the Tuskegee Airmen received its training here and would go on to fight with distinction performing bomber-escort, dive-bombing, and strafing missions in Europe.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

![United We Win [World War II Poster] (1943)](/assets_c/2009/06/image_07_10_010_united-thumb-360x470-823.jpg)