SECTION 04

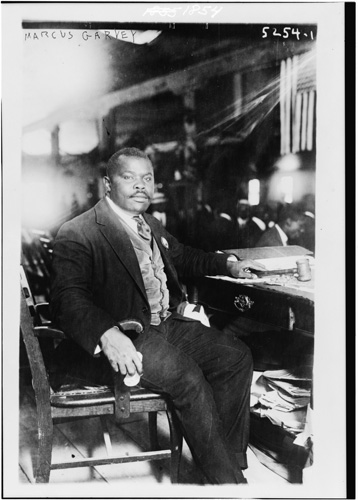

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Garvey, August 5, 1924.

Source: August 5, 1924, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Amidst the disappointments of the postwar period, Marcus Garvey emerged on the streets of Harlem as the leader of the largest black organization of the twentieth century. Born in 1887, in St. Ann’s Bay, Jamaica, Garvey had been employed as a journalist, printer and labor organizer in the Caribbean and England before returning to Jamaica to establish the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), an organization rooted in the notion that black people throughout the world should have the right to self- determination. Impressed with Booker T. Washington’s philosophy of self-help and black-owned enterprises, Garvey found little response in his native homeland, and decided to try his hand at organizing in America. There, within four years, his program of militant Black Nationalism had attracted hundreds of thousands of devoted followers with chapters in countries throughout the world. Garvey, by asserting “race first” Pan-Africanism, sought to create a separate sphere of community progress for African Americans, responding to the systematic exclusion of Black people from economic and political power. Garvey was not interested in having a “slice of the pie” of the United States polity; he was interested in creating an entirely separate nation-state.

Garvey initiated a series of enterprises that captured the imagination of the black masses: the Black Star Line, a steamship company; the Negro Factories Corporation; the Black Cross Nurses; and the African Legion. He sent UNIA leaders to Liberia and Sierra Leone to explore the possibilities of black Americans migrating “back to Africa.” His controversial newspaper, the Negro World , was translated into several languages, but was banned by British and French colonial officials in Africa and the Caribbean. Garvey advocated racial separatism and championed the slogan: “Africa for the Africans at Home and Abroad.” Garvey’s militant black nationalism resulted in harassment and surveillance by U.S. and British intelligence agencies. Desperately trying to find any way to get rid of the leader who had managed to organize the black working class, the federal government indicted Garvey on charges of mail fraud, generated by complaints about fiscal mismanagement of the Black Star Line. Convicted and imprisoned in 1925, he was deported from the United States two years later. Although he attempted to rebuild his movement, first in Jamaica and later in England, the UNIA never regained its popularity or prominence. In 1940 Garvey died after several severe strokes.

While Garvey’s “Back to Africa” movement was little more than an idea, for his followers, “Africa for the Africans” was an important link for black Americans who were denied both citizenship and a history in their own communities. While Jim Crow enforced the restriction of Black movement, the industrialization of the North led to the Great Migration, and mobility was very much tied to the mobilization of struggles for equality. Garvey’s expansive notions allow for the conception of a Black nation that exists not only in the specific and bounded locale of Black businesses, schools, and parades, giving Black pride a public arena, but also as a trope for an imagined community. Garvey’s notions of Black Nationalism and self-determination would later influence American figures like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, as well as African independence leaders Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta.