SECTION 07

Harlem Renaissance

The new urbanity of black America fostered an awakening of African American arts and letters. The first wave of Southern migrants seeking to escape the brutal economic and social apartheid of the Jim Crow South had created vibrant, although still segregated, communities, throughout the Northeast and Midwest. Harlem would become the Mecca, politically, culturally, and symbolically, of a new day in Black America. By 1930, there were over 200,000 black Americans living in Harlem. Black politicians, journalists, writers, scholars, collectors, and intellectuals converged on 125th Street, brought to New York City by the promise of a new dawning of opportunities for black Americans and ready to fight the injustices that they still encountered in their new surroundings. Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. DuBois, the NAACP, Charles Johnson and more, found homes on the streets of Harlem. This emerging black middle class was intent on advocating a political agenda of racial equality and black pride.

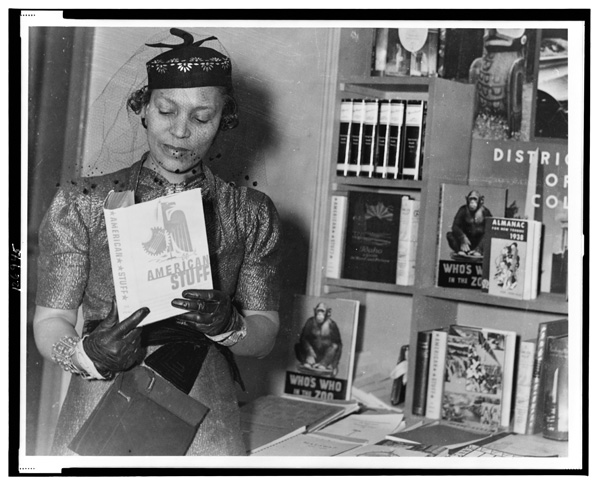

Zora Neale Hurston.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Following the disappointment of the first World War’s lack of impact on domestic inequities, a brilliant literary and artistic movement, the Harlem Renaissance, brought public attention the creative works of poets, novelists, and writers such as Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, Nella Larsen, Zora Neale Hurston, Alain Locke and Claude McKay. African American artists understood that expressions of black culture were directly linked with the political and social movement for freedom. Attempting to use literary and visual means of art production to historicize and articulate the black American experience, Harlem Renaissance artists sought to distinguish a unique African American artistic tradition rooted in an African past. Attempting to explore the black identities and cultural textualities, but also challenge notions of white supremacy and inequity, these artists were inherently political. Although they pushed for a distinct African American cultural tradition, the work of the Harlem Renaissance artists also insisted that the black cultural experience was central to the American experience at large.

Dependent on white patronage, however, the literary and cultural figures of the Renaissance shied from the scathing critique of white America offered up by figures like Marcus Garvey. Nevertheless, the insistence on a distinctively black cultural history that was central to an American identity informed and shaped the work of later black art movements and solidified the relationship between black art forms and political protest. Black art was by nature political in its refusal to dismiss the significance of black contributions to present day America.

Related Resources

Zora Neale Hurston.

Zora Neale Hurston, at New York Times Book Fair, November 1937.

Zora Neale Hurston was one among many poets, novelists, and writers who were part of the Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African American arts and letters.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.