SECTION 13

Pop-Culture

Marian Anderson performance at the Lincoln Memorial.

Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

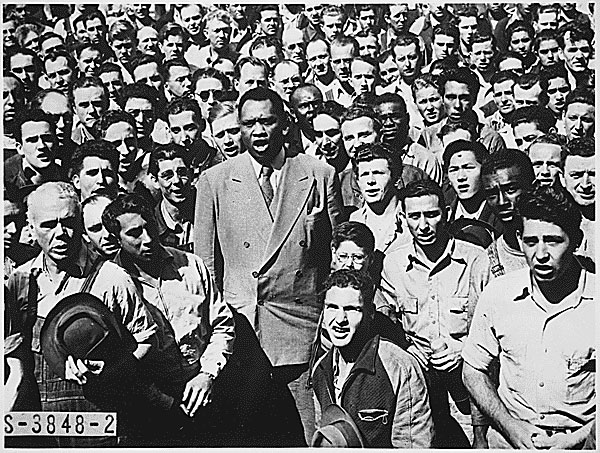

Paul Robeson leading shipyard workers in singing the Star-Spangled Banner, September 1942.

Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

The great actor and singer Paul Robeson observed that black culture and “the Negro idiom” formed the basis for most of America’s popular music, dance, and the theater. “At another stage of the arts there is no question, as one goes about the world, of the contributions of the Negro folk songs, of the music that sprang from my forefathers in their struggle for freedom – not songs of contentment – but songs like ‘Go Down, Moses’ that inspired Harriet Tubman, John Brown, and Sojourner Truth to the fight for emancipation,” Robeson wrote in 1952. “The culture with which we deal comes from the people … in fighting for our cultural heritage [we] fight for our own rights, for the rights of the negro people, the power of the masses of America, of a world where we can all walk in complete dignity.” Art and music became an important protest tool in addressing the history of oppression of black freedom.

While white patrons loved the music, theaters and concert halls remained segregated for the audiences. Performers like Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong found themselves subject to the racist degradation of entering and exiting through separate entrances, playing in segregated concert halls, and having to travel on segregated cars from one gig to another. While they were heralded at the Cotton Club, a venue for exclusively white patrons in the middle of Harlem, as the greatest American performers, their everyday experiences with racism spoke to the contradictions in American culture and politics.

Youth, in particular, embraced jazz and bebop. Ironically, because many white Americans readily accepted the stereotype that black people were “natural” entertainers, athletes and dancers, ballrooms and jazz clubs and eventually stadiums during the 1930s and 1940s were among the most integrated places in America. By the early 1950’s, music of all kinds had the distinctive sound of a jazz band resonating in its baseline.

The arena of sports also provided new inroads for cultural integration. James Cleveland “Jesse” Owens was born in Alabama in 1913, the son of a sharecropper. The Owens family moved to Cleveland, Ohio in 1931 during the Great Migration, and Jesse became a star athlete while still in high school. As a sprinter at Ohio State University he set world records in the 100-yard dash, the 200 dash and the broad jump. At the Big Ten Championships on 25 May 1935, he broke five world records, and equaled a sixth in track and field competition – all within 45 minutes. At the controversial Olympic Games held in Berlin in 1936, Owens stunned the world by winning four gold medals. His triumph was a symbolic defeat of the Nazi ideology of a master race. However, as much as Owens’ victory provided the figurative triumph of democracy over fascism, it did little to shake the ground of racial injustices at home. Owens was forced to enter the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, the site of his victory parade, through the service door. The hero was never invited to the White House.

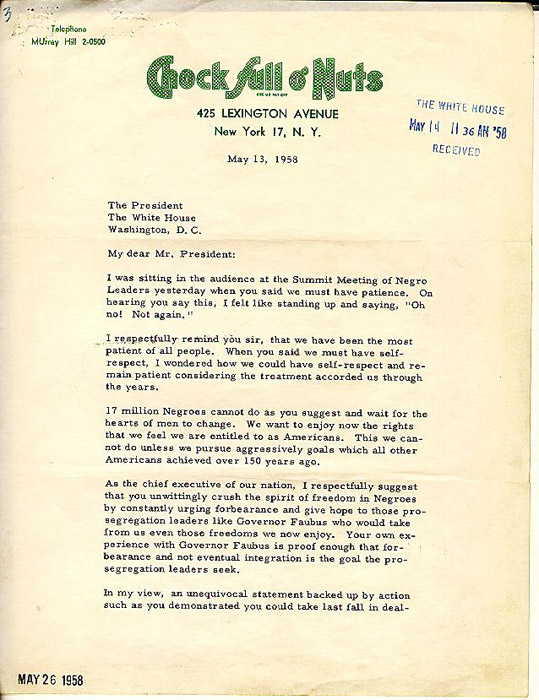

Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower (Slide 1).

Source: White House Central Files, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abiline, KS.

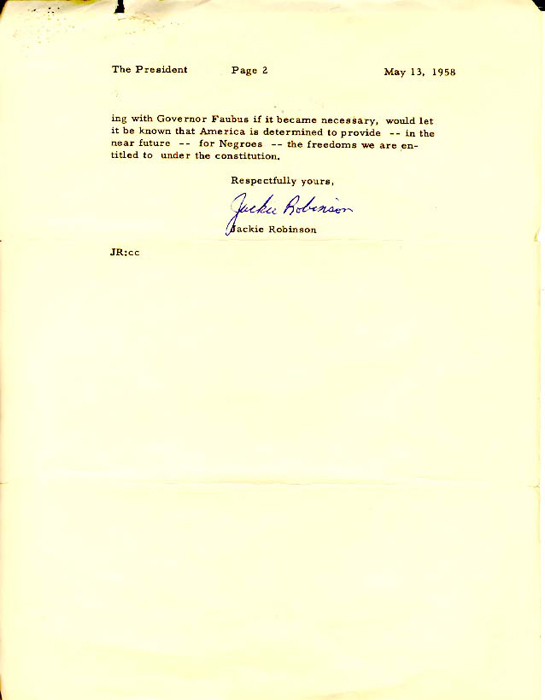

Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower (Slide 2).

Source: White House Central Files, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abiline, KS.

It would be another eleven years before the watershed of sports integration occurred. For several decades civil rights groups and leftist organizations pressured professional baseball to desegregate until finally, in April 1947, Jackie Robinson began his career with the Brooklyn Dodgers. For three years racist fans and players harassed him, but with grim determination and courage he refused to respond to their racial provocations. Despite the constant intimidation, he earned Rookie of the Year honors and led the league in stolen bases. Two years later, he was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. Robinson’s success paved the way for thousands of African Americans to enter professional sports.

Particularly after World War Two, baseball and jazz became, to the world, the quintessential symbols of American culture. As leisure and entertainment became increasingly open to notions of integration, with youth at the forefront of that acceptance, it was reflected within politics. By the 1950’s, it was clear that segregation would not last, and that Black Americans would continue to be vital forces in creating America’s past, present and future.

Related Resources

Paul Robeson leading shipyard workers in singing the Star-Spangled Banner, September 1942.

Paul Robeson, world famous baritone, leading Moore Shipyard [Oakland, CA] workers in singing the Star Spangled Banner, here at their lunch hour recently, after he told them: "This is a serious job---winning this war against fascists. We have to be together." Robeson himself was a shipyard worker in World War I.

Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Marian Anderson performance at the Lincoln Memorial.

Singer Marian Anderson performing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, April 10, 1939.

After the Daughters of the American Revolution denied Marian Anderson permission to perform before an integrated audience at the DAR Constitution Hall, the Roosevelt administration intervened and staged her performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The critically-acclaimed concert was attended by over 75,000 people.

Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower (Slide 1).

Jackie Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower urging more aggressive civil rights protections, May 13, 1958.

Source: White House Central Files, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abiline, KS.