SECTION 01

School Desegregation Movement: Brown vs. The Board Of Education

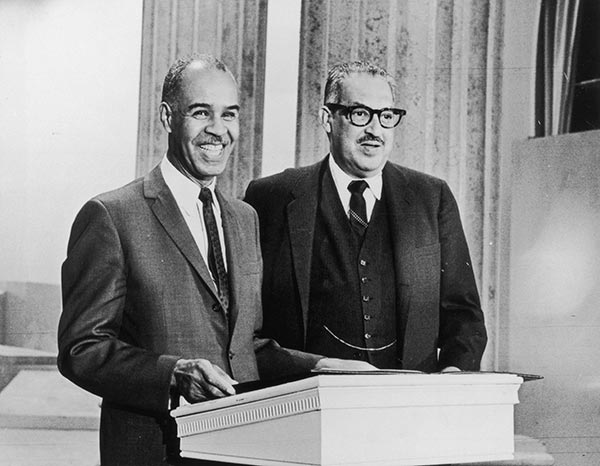

NAACP chief Executive Roy Wilkins presents the Freedom Bell Award to Judge Thurgood Marshall.

Source: CORBIS.

A new phase of American history dawned on May 17, 1954, in Topeka, Kansas, thanks to a legal decision that would shape public education from that time on. Black parents and civil rights lawyers in Virginia, Kansas, Washington, D. C., South Carolina, and Delaware had challenged the legality of segregated public school systems during the early 1940s and 1950s. By late 1952, all these cases had reached the U.S. Supreme Court. After a year and a half of hearings, the high court finally handed down an unanimous decision in what became popularly known as Brown v. Board of Education . The high court declared in its ruling: "In the field of education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place." The decision marked a clear victory for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had been fighting the notion of legalized segregation since the organization's inception in 1910. By 1955, the Supreme Court urged the adoption of desegregation plans by public schools "with all deliberate speed." By the 1956-57 school year, 723 southern school districts had been desegregated, and 300,000 black children were either attending formerly white schools or were part of a "desegregated" school district.

However, in most cases, the desegregation of schools was not accomplished without extreme reactionary resistance. Less than a week before the 1957 school year began, the Arkansas state court ordered Little Rock to reverse the city's desegregation plan. A federal court overruled the state jurists, but Governor Orval Faubus, a racial moderate who had gained his greatest electoral support from blacks and middle-to-upper-class whites, ordered the state's National Guard to forbid nine black children to enter the Little Rock Central High School. Armed with automatic rifles, the soldiers and a mob of unruly white people pelted and pushed the young students away from the schoolhouse before national television cameras. In late September 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower very reluctantly ordered the state's 10,000 guardsmen to submit to federal authority, and army troops were called to disperse the angry white mobs terrorizing the black students. Little Rock schools were closed during the 1958-59 school year, and black students did not attend the schools until August of 1959.

As the movement for desegregation continued to gain momentum, the measures employed by white supremacists became more violent. The Ku Klux Klan reasserted itself as a powerful secret (and sometimes not so secret) organization, committing a series of murders and bombings of black homes and churches. Despite these terror tactics, civil rights activists continued to make strides against legalized segregation.

Related Resources

Interview conducted in 1977. Stories from the Collection: Columbia University Oral History Research Office, CD, 1998 track 05

Stories from the Collection: Columbia University Oral History Research Office, CD, 1998 track 10