SECTION 13

Black Opposition to Vietnam

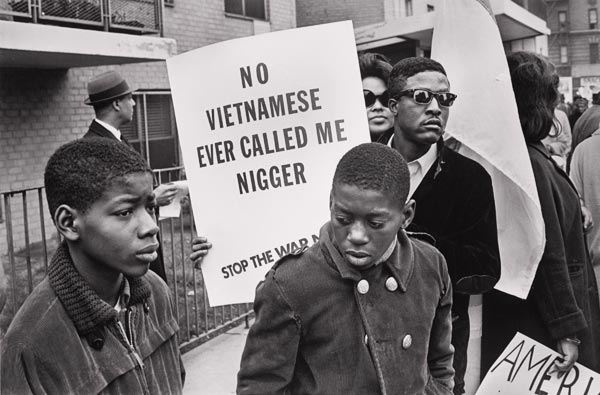

Demonstrators at the Harlem Peace March to End Racial Oppression, 1967.

Source: Courtesy of Builder Levy, photographer.

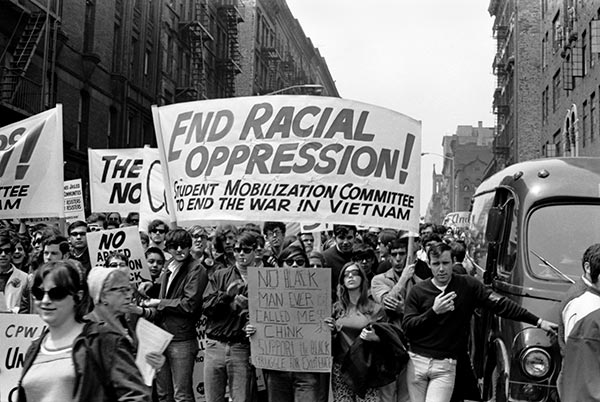

Harlem Peace March to End Racial Oppression, 1967.

Source: Courtesy of Builder Levy, photographer.

By July 1965, SNCC members had produced their first uncompromising statement on the war, declaring that blacks should not "fight in Vietnam for the white man's freedom, until all the Negro people are free in Mississippi." From the outset, the burden of the conflict was borne disproportionately by African Americans and working-class and poor whites. During the early years of the war, students enrolled in college could obtain deferments from military service. Many middle- and upper-class whites were also able to fulfill military obligations by joining the Army Reserve or the National Guard. As a result, in 1967, 64 percent of all eligible African-Americans were drafted, but only 31 percent of eligible whites. During 1965-66, the casualty rate for blacks was twice that of whites. Malcolm X was the first prominent African American leader to denounce the Vietnam War, and others soon followed his lead.

During the bitter national debate on Vietnam, all public leaders within black America were forced to choose sides. Black progressives in electoral politics began to speak out in opposition to the war. As a dedicated pacifist, Martin Luther King took a strong public stand against it. At the annual SCLC executive board meeting held in Baltimore on April 1-2, 1965, King expressed the need to criticize the Johnson Administration's policies in Southeast Asia, much to the dismay of colleagues who believed his antiwar sentiment would jeopardize the organization's funding. In January 1966, King published a strong attack on the Vietnam War. In it he stated that Black leaders could not become blind to the rest of the world's issues while engaged solely in problems of domestic race relations. While the initial response to King's statement was negative, by the spring of 1966 the SCLC' s executive board had come out officially against the war. King understood that the massive military spending on the war in Vietnam meant that the nation had far fewer resources available to attack domestic poverty, illiteracy, and unemployment. King concluded that the Vietnam conflict had to end immediately. On April 4, 1967, speaking at Harlem's Riverside Church, King announced: "It would be very inconsistent for me to teach and preach nonviolence in this situation and then applaud violence when thousands of thousands of people, both adults and children, are being maimed and mutilated and many killed in this way." Eleven days later, Dr. King organized a rally of 125,000 in protest against the war.

In an expansion of his message concerning race and the war in Vietnam, King began to link the oppression of the poor to the global oppressiveness of capitalism as exhibited in the U.S. action in Southeast Asia. When Black Memphis sanitation workers voted to strike on February 12 to protest against low wages and the accidental deaths of two black garbage men 12 days before, they asked the SCLC for help. King and his closest associates arrived in the city to help mobilize popular support for the strike. The pacifist minister, who had once struggled for desegregated buses, was now, 13 years after Montgomery, organizing militant black urban workers, building a national poor people's vision, and defying a president. On April 4, 1968, while standing on a balcony outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, King was assassinated by a white man, James Earl Ray, when the police officers who had been guarding the minister were absent.

Black people across the nation felt the grievous loss to the cause for racial freedom. As word spread throughout the country of the esteemed civil rights activist's murder, cities erupted into violence reminiscent of the previous summer's urban unrest. Ministers, activists, and entertainers were dispatched throughout the nation to calm crowds outraged by King's assassination.

Despite the death of the great leader, the antiwar struggle continued. Using the Reverend's rhetoric linking inhumane foreign policy to the injustices of the American domestic social landscape, students continued to raise questions and demonstrate against the war they saw as an extension of American racism. On May 14, as Jackson State College students protested the injustices of the war and American racism, the police opened fire on the rally, killing two and injuring 12. Occurring right after the Kent State shootings, where four students were killed by the Ohio National Guard as they protested, the events at Jackson State set off a widespread outrage that linked the war to police violence and domestic injustice. The protest of a spectrum of black leaders, athletes, activists, artists, and entertainers helped force the federal government to start withdrawing troops from Vietnam in late 1969.

Related Resources

Demonstrators at the Harlem Peace March to End Racial Oppression, 1967.

A young demonstrator carries a placard that reads "No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger" at the Harlem Peace March to End Racial Oppression on April 27, 1967. The statement was taken from boxer Muhammad Ali's original statement about his refusal to participate in the Vietnam War, "Ain't no Vietcong ever called me nigger."

Source: Courtesy of Builder Levy, photographer.

Harlem Peace March to End Racial Oppression, 1967.

A young man carries a placard that states "No Black Man Ever Called Me Chink" during the Harlem Peace March to End Racial Oppression on April 27, 1967. The statement was taken from boxer/activist Muhammad Ali's original statement about his refusal to participate in the Vietnam War, "Ain't no Vietcong ever called me nigger."

Source: Courtesy of Builder Levy, photographer.