SECTION 01

Social and Economic Issues of the 1980s and 1990s

The vast changes in the global economy in the last decades of the twentieth century have had a profound impact on the social character of black America. In 1970, for example, as a result of the gains of the civil rights movement, nearly 40 percent of all black workers were employed in blue collar jobs, with millions of them in heavy industry such as steel, automobile production, electrical and non-electrical machinery, appliances, food and tobacco manufacturing, and textiles. Hundreds of thousands of blacks were also employed in the energy industry and in the food processing industry. Millions of these jobs were located in the industrial and manufacturing centers of the Northeast and Midwest, in urban areas with high percentages of African Americans, which were the first casualties for what economists soon described as “deindustrialization.” Between 1973 and 1980, over four million jobs disappeared in the United States when American companies moved their operations outside the country. New York City alone lost 40,000 to 50,000 jobs in the apparel and textile industries. Corporations increasingly divested their profits from U.S. -based subsidiaries and reinvested in operations abroad. In the 1970s, over thirty million total jobs were eliminated through factory closings, relocations, and then phased elimination of operations. The shrinking of U.S. -based industries had a deep impact on labor unions, as the percentage of union members within the American labor force decreased by half in only two decades. Hardest hit were African American blue-collar workers, because in 1983, over 27 percent of all blacks in the U.S. labor force were union members.

The erosion of the public sector and the loss of millions of urban jobs contributed to a profound increase in class stratification within the national black community. The African American community was overwhelmingly working class in composition in the 1970s. By the late 1990s, the socio-economic profile of black America had changed considerably. About 51 percent of all black employees sixteen years old and over were classified as white-collar workers. Approximately 60 percent of these were white-collar sales and clerical personnel; many in this group were non-union workers with limited benefits and wages. However, another 20 percent of the black labor force, nearly three million workers, was classified as professional and technical workers and administrators. The percentage of blue-collar workers had declined to 28 percent of the black labor force. Black farm laborers, farmers, and agricultural managers, who in 1940 had represented one-third of the entire black workforce, had virtually disappeared, with only about 80,000 jobs remaining. During this period, the black business sector had mushroomed.

By 1992 the number of black-owned businesses had grown to 621,000. The number of black-owned real estate, insurance, and financial lending companies had quadrupled in only fifteen years, and this sector’s total gross receipts had increased six-fold. A small number of African American executives by the late 1990s had become chief executive officers and presidents of major corporations, such as AOL Time Warner and American Express. An even smaller number of black celebrities—superstar athletes such as Michael Jordan and Earvin “Magic” Johnson, and television personalities such as Oprah Winfrey and Bill Cosby, and pop star Michael Jackson—were each worth hundreds of millions of dollars. For the first time in U.S. history, a “black bourgeoisie” had come to exist.

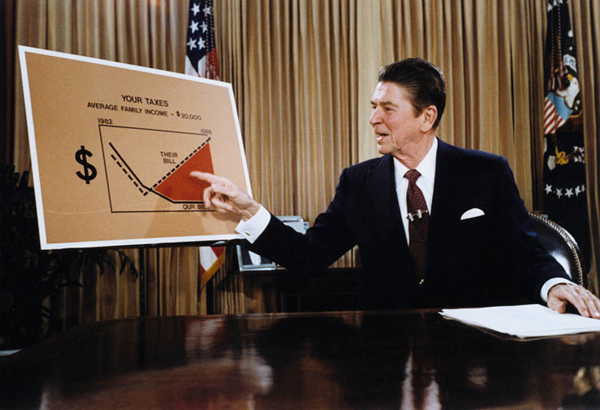

Reagan gives a televised address, July 1981.

Source: Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, National Archives and Records Administration.

Nevertheless, the deindustrialization of many U.S. cities had serious consequences for the African American population. Deprived of their tax revenues from industries and manufacturing companies, city governments reduced expenditures for public institutions of all kinds—schools, hospitals, parks, libraries, public universities, and public housing. With the election of Ronald Reagan as president in 1980, the new conservative administration quickly moved to reduce federal government spending on urban development and social services. The Reagan Administration terminated the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act program, a successful job training program that had been funded in 1982 at $3.1 billion; eliminated $2 billion from the federal food stamps program; reduced federal support for child nutrition programs by $1.7 billion over a two-year period; and closed down the Neighborhood Self Help and Planning Assistance programs, which provided technical and financial help to inner cities. In the first year of the Reagan Administration, the real median income of all black families fell by 5.2 percent. The number of Americans living below the federal government’s poverty line grew by over two million in a single year. In 1982, over 30 percent of the total black labor force was jobless at some period during that year. In June 1982, Congress reduced federal assistance programs by 20 percent and cut federal assistance to state and municipal governments.

Beginning in the 1980s, a strong white backlash to the civil rights movement expressed itself in opposition to school desegregation in the North, hostility to increased integration in higher education and professional occupations through affirmative action programs, and resurgence of racial violence. The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups initiated national campaigns of terror, drive-by shootings of African Americans, and firebombing of black churches and residential areas. Millions of white Americans had become convinced that “too much” had been given to blacks in recent years. Middle-class African Americans also encountered more subtle, yet unmistakable, patterns of racial discrimination that severely restricted their upward mobility. Sociologist Larry Bobo has described this racial ceiling on group advancement as “laissez faire racism.” The examples today, which have been documented by numerous studies, are almost endless: white car dealerships that charge blacks hundreds of dollars more for automobiles than they do whites; hospitals that routinely provide substandard treatment for minorities; insurance companies that systematically charge black consumers higher rates than whites to insure homes of identical market value; grocery store chains that transport older produce from white suburban shopping-mall markets to groceries in predominantly black communities; the denial of employment opportunities at senior levels of management and administration in large companies and institutions.

Many middle-class blacks, confronted with the steady deterioration of public services, schools, and the elimination of jobs in central cities, relocated to the suburbs. However, because white real estate firms, banks, and financial lending institutions continued informal policies of residential discrimination, many upper- to middle-income blacks found themselves moving from segregated ghettoes to racially segregated suburbs or planned communities. Black working-class families without the material resources or credit to purchase homes outside economically depressed areas found themselves living in what, at times, had become almost urban wastelands.

In huge districts of America’s major cities, neighborhoods had become desperately poor—Chicago’s South Side, East New York in Brooklyn, the South Bronx, South Central Los Angeles, East Oakland, and nearly all of Detroit. Families attempting to upgrade their residences or start businesses in these neighborhoods were forced to rely on “predatory lenders,” finance companies charging outrageously high interest rates on borrowed money. In such inner city communities, businesses of nearly every type, other than personal services such as restaurants, barber shops, beauty salons, and funeral homes, largely disappeared. In some inner cities in the 1990s, between 30 to 43 percent of a neighborhood’s total adult population was no longer in the paid labor force. Millions survived in the informal economy, generating a subsistence income through activities as diverse as braiding hair, childcare, collecting and selling recyclable bottles and cans, catering food, auto repair, moving, producing and selling crafts, etc. for many who had once held stable blue-color jobs, low-wage service jobs, such as in the fast-food industry, were among the few alternatives. Ironically, some fast-food restaurants in ghettoes refused to hire local residents because employers feared that they would give away food to unemployed and low-income relatives and friends.

Such widespread poverty, such intense patterns of hunger and homelessness, fostered a new form of social devastation: trafficking in illegal drugs. In the early 1980s, a new addictive product, “crack,” a rock-type of cocaine, was introduced into inner-city neighborhoods. Unlike powdered cocaine, the fashionable drug of choice of the wealthy, crack was very inexpensive, readily available, and highly addictive. Within a few years, several hundred thousand African Americans had become addicted to crack, and relatively few drug treatment centers were available. With the decline in employment and educational opportunities, some young people saw selling drugs as the only way to make a decent income, and violence, once relatively rare in black working-class communities, increased significantly. Although several inner-city communities became the marketplace for the lucrative international traffic in illegal substances, the overwhelming bulk of the profits were reaped by those outside these communities, such as international crime cartels and the banks that launder their money. Inner-city communities became the targets of police sweeps and searches. Many community residents found themselves caught between a desire to rid their neighborhoods of the plague of drugs and violence, on one hand, and what was often seen as indiscriminate violence by the police, on the other. Though a small minority of young men were actively involved in criminal activities connected with the drug traffic, virtually all black male youth were subject to being stigmatized as criminals by the police and media. Young black men particularly were subjected to racial profiling: routine searches without any probable cause except the color of their skin. A series of highly publicized cases of excessive use of force by the police, sometimes leading to the death of innocent victims, in New York City, Los Angeles, Miami, and Cincinnati, generated mass protest mobilizations.

Federal and state governments responded to the increased levels of criminal violence by making the penalties for drug sale and possession more severe, by eliminating parole, and by constructing a vast network of new prisons. Legislatures passed new mandatory minimum sentencing laws, requiring convicted felons to serve lengthy prison terms before becoming eligible for release. Juveniles were increasingly treated as adults, and were subjected to many of the same penalties. Developments in New York State during these years were typical of what occurred throughout the nation. Between 1817 and 1981, the state had constructed thirty-three prisons; between 1981 and 1999, it built thirty-eight new correctional facilities. New York’s prison population grew in two decades from 13,500 to 74,000. Between 1988 and 1998, the state increased the budget of the Department of Correctional Services by $761 million. During that period, support for public higher education decreased by roughly the same amount.

President Clinton signs the 1996 PRWORA legislation.

Source: United States Federal Government.

Throughout the country, the total population of prisoners reached 650,000 in 1983, one million in 1990, and two million by 2001. One-half of these prisoners were African-Americans. By 2000, one-third of all black males in their twenties were under the control of the criminal justice system—either in prison or jail, on parole, probation, or awaiting trial. The major reason for this disproportion in incarceration is the stark racism that continues to pervade the criminal justice system. Though African Americans constitute approximately 14 percent of all illegal drug users, they comprise approximately one-third of all drug arrests and over 50 percent of all drug convictions in federal and state courts. The socio-economic and political consequences of mass incarceration for the black community have been profound. Hundreds of thousands of households have been destroyed; thousands of children separated from their parents and raised in foster care. In ten states, convicted felons lose the right to vote for life, and as a result, by 2000 over 1.4 million African Americans had been permanently disenfranchised. For several million blacks with criminal records, better paying jobs were no longer available even years after their release and rehabilitation. Given the widespread unemployment, high rates of incarceration, and the lower life expectancy of black men, more and more black women found themselves in the position of having to raise children alone. Because black women historically have been the lowest paid workers, with the highest rates of unemployment, some have been forced to depend on government subsidies to supplement their incomes, often from informal sources of work. In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which severely limited government assistance to families. In the absence of guaranteed employment at wage rates that would allow households to subsist, women and children became increasingly vulnerable.

Related Resources

Bill Cosby.

Dr. William H. Cosby speaks at Frederick Douglass High School during his visit to the school.

Source: Scott King, United States Navy.

Reagan gives a televised address, July 1981.

Reagan gives a televised address from the Oval Office, outlining his plan for Tax Reduction Legislation in July 1981.

Source: Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, National Archives and Records Administration.