SECTION 05

Apartheid

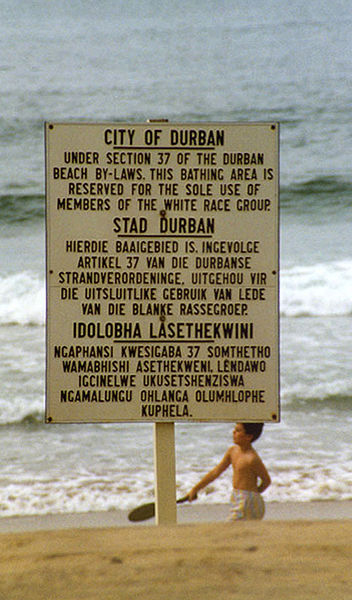

Sign in Durban that states the beach is for whites only under South African apartheid laws.

Source: Guinnog.

As activists and intellectuals were doing groundwork to re-constitute the black freedom movement through politics and coalition building, the single- most important international issue that concerned black America after the end of the Vietnam War was South African apartheid. For nearly forty years, the minority regime in South Africa had imposed a rigidly authoritarian form of racial segregation on millions of African people. Thousands of South African black people were executed, imprisoned or exiled from their country as they struggled to overthrow an oppressive colonial government. As the Afrikaner government attempted to suppress the growing mass collective action of groups like the African National Congress (ANC), the South African Communist Party and others, outraged black and white Americans began to speak out.

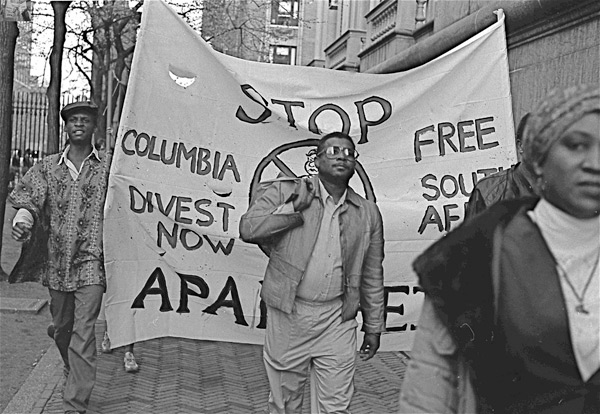

However, in the 1980s, the Reagan Administration initiated a policy of “constructive engagement” with the apartheid regime of South Africa, which encouraged American investment in the country, thus providing economic support for the apartheid government. This prompted a series of demonstrations against apartheid and U.S. investment in South Africa. Following Reagan’s re-election, in 1984, a core of black progressives mapped out a strategy to attack the administration’s links with apartheid South Africa. The group was led by Randall Robinson, executive director of TransAfrica; Mary Frances Berry, a civil rights commissioner; and District of Columbia representative Walter Fauntroy. The coalition leaders staged a small symbolic demonstration in front of the South African embassy in late November 1984, and they were ‘pleasantly surprised’ when officials panicked and called the police. Their arrests sparked a series of nonviolent demonstrations across the United States. Within two weeks, protests were staged at South African consulates in more than one dozen cities, including Salt Lake City, Boston, Chicago, and Houston.

On college campuses, thousands of students demonstrated against university and company investment in firms that did business inside South Africa. Divestment legislation amounting to $400 million in public funds was secured in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Michigan, Maryland, Philadelphia, and a dozen other smaller cities. Jesse Jackson put pressure on the Democratic leadership to demand immediate freedom for Nelson Mandela, the political spokesperson for the ANC and future South African President who had been imprisoned on Robben’s Island for over two decades. Other black congressman added to that pressure for other political prisoners as well.

Due to pressure from anti-apartheid protestors, in 1985 local municipal governments began to prohibit deposits of city funds in banks that loaned money to South Africa’s government. By the end of the year many of America’s largest banks, including Bank of America and Citibank, had been forced to terminate loans to South Africa, and many major U.S. corporations stopped doing business in South Africa for fear of public disapprobation. On 2 October 1986 the U. S. Congress passed, over President Reagan’s veto, the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act that outlawed new bank loans to the public and private sector in South Africa. TransAfrica, an African American nonprofit lobbying organization that advocates African and Caribbean interests, played an important role in the passage of the legislation.

In the early 1990s, the African National Congress (ANC), with the aid of international solidarity movements, was successful in overturning the apartheid government of South Africa. Nelson Mandela, whose freedom had long been sought by African Americans and others, was triumphantly welcomed in the United States.

Related Resources

Sign in Durban that states the beach is for whites only under South African apartheid laws.

Source: Guinnog.