Image Archive

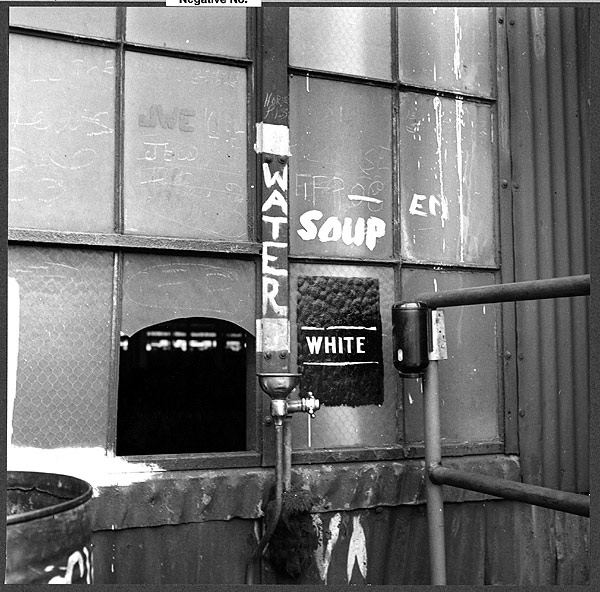

Water fountain for whites, Baltimore, Maryland, 1943.

Throughout the South, separate public facilities and accommodations were commonplace, such as this water fountain marked for whites in a Baltimore, Maryland shipyard in 1943. Source: Arthur Siegel, May 1943, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Throughout the South, separate public facilities and accommodations were commonplace, such as this water fountain marked for whites in a Baltimore, Maryland shipyard in 1943. Source: Arthur Siegel, May 1943, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

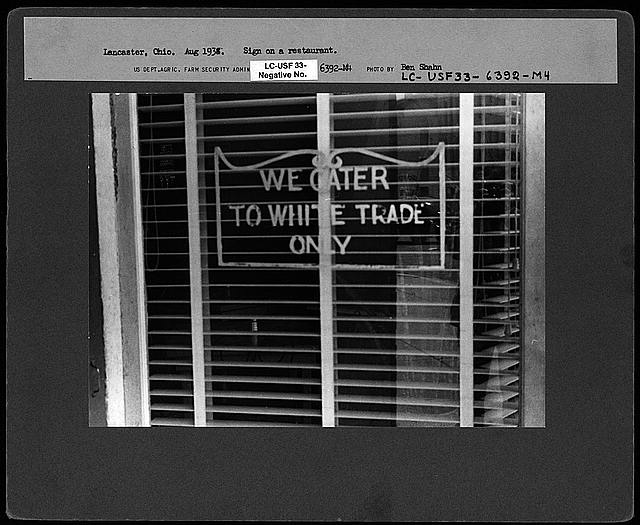

Sign on restaurant indicating "We Cater to White Trade Only," Lancaster, Ohio, 1938.

During Jim Crow segregation, some business establishments did not service black patrons at all. This sign on a restaurant in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1938, is clear about serving whites only. Source: Ben Shahn, August 1938, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

During Jim Crow segregation, some business establishments did not service black patrons at all. This sign on a restaurant in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1938, is clear about serving whites only. Source: Ben Shahn, August 1938, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

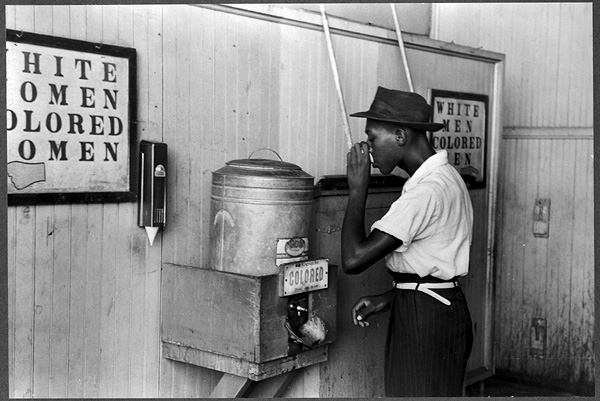

Man drinking at a water cooler reserved for "Colored," Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 1939.

Separate water fountains for blacks and whites, providing such basic a human need as water, highlighted how far-reaching racial discrimination was during the Jim Crow era. Source: Russell Lee, July 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Separate water fountains for blacks and whites, providing such basic a human need as water, highlighted how far-reaching racial discrimination was during the Jim Crow era. Source: Russell Lee, July 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

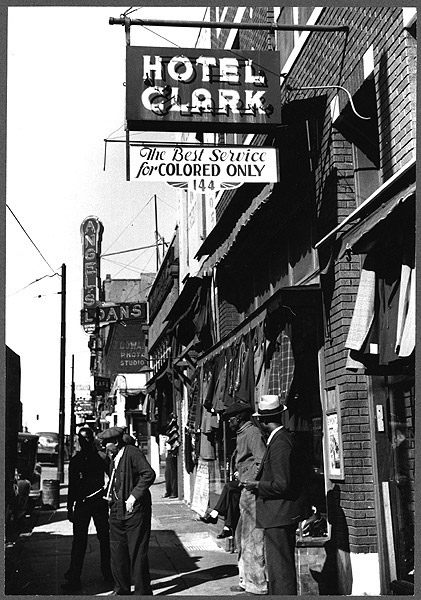

Hotel for "Colored" patrons, Memphis, Tennessee, 1939.

Barred from the same hotels available to whites, African Americans relied on hotels such as the Hotel Clark on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee to provide accommodations. Source: Marion Post Wolcott, October 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Barred from the same hotels available to whites, African Americans relied on hotels such as the Hotel Clark on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee to provide accommodations. Source: Marion Post Wolcott, October 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

"White Ladies Only" restroom at bus station, Durham, North Carolina, 1940.

The "White Ladies Only" sign on the restroom at this bus station in Durham, North Carolina, in 1940, was typical of Jim Crow segregation of public bathrooms throughout much of the South. Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

The "White Ladies Only" sign on the restroom at this bus station in Durham, North Carolina, in 1940, was typical of Jim Crow segregation of public bathrooms throughout much of the South. Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

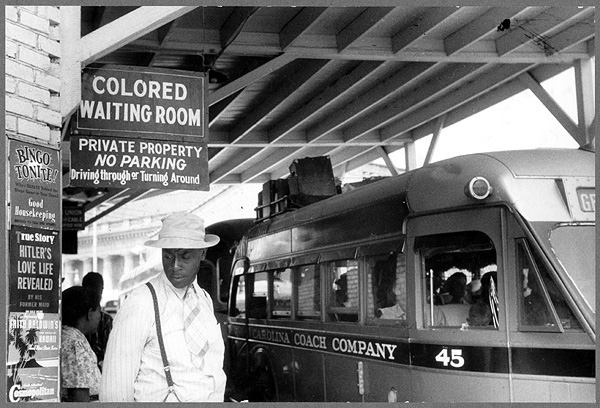

"Colored Waiting Room" at bus station, Durham, North Carolina, 1941.

African American travelers throughout the South were directed to "colored only" waiting areas at bus stations, such as this one in Durham, North Carolina, in 1940. Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

African American travelers throughout the South were directed to "colored only" waiting areas at bus stations, such as this one in Durham, North Carolina, in 1940. Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

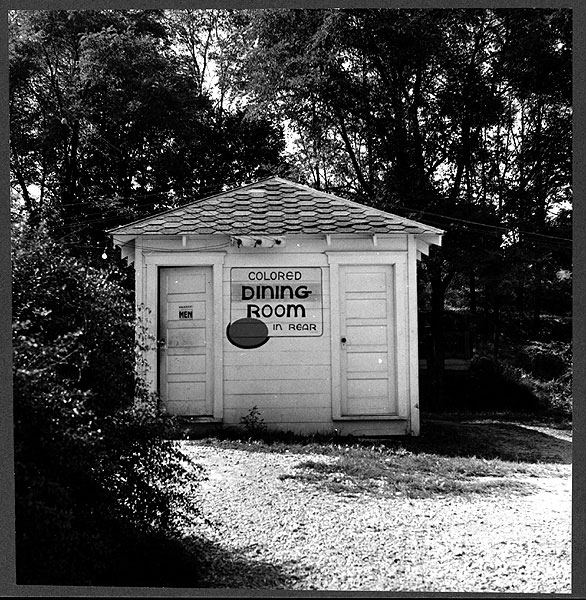

"Colored Dining Room in Rear."

A rest stop for Greyhound bus passengers on the way from Louisville, Kentucky to Nashville, Tennessee, with separate accommodations for colored passengers. When patronizing restaurants and diners that also catered to whites, African Americans usually entered through separate entrances (often through the kitchen or through a rear entrance), and ate in separate areas. Source: Esther Bubley, September 1943, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

A rest stop for Greyhound bus passengers on the way from Louisville, Kentucky to Nashville, Tennessee, with separate accommodations for colored passengers. When patronizing restaurants and diners that also catered to whites, African Americans usually entered through separate entrances (often through the kitchen or through a rear entrance), and ate in separate areas. Source: Esther Bubley, September 1943, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

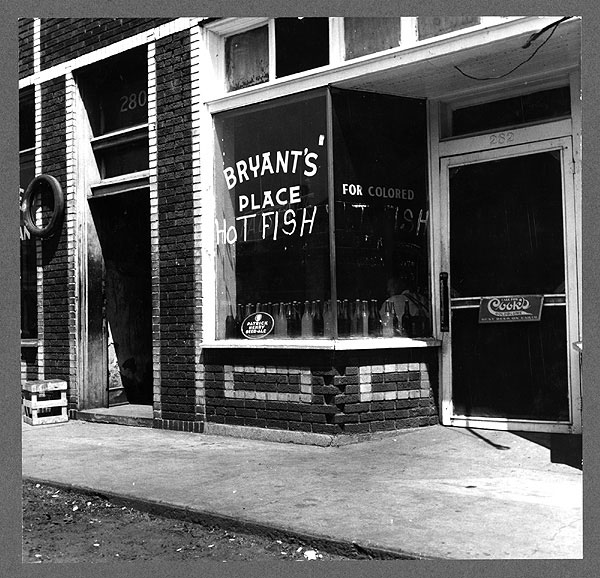

A fish restaurant for Negroes, Memphis, Tennessee, 1937.

Subjected to second-class treatment at restaurants and diners that also catered to whites, many African Americans chose instead to patronize business establishments that catered specifically to blacks, such as this fish restaurant in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1937. Source: Dorothea Lange, June 1937, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Subjected to second-class treatment at restaurants and diners that also catered to whites, many African Americans chose instead to patronize business establishments that catered specifically to blacks, such as this fish restaurant in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1937. Source: Dorothea Lange, June 1937, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

A cafe in the warehouse district with separate doors for "White" and "Colored".

A cafe in Durham, North Carolina with separate entrances for "White" and "Colored," in 1940, typical of eating establishments throughout the South during the Jim Crow era. Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

A cafe in Durham, North Carolina with separate entrances for "White" and "Colored," in 1940, typical of eating establishments throughout the South during the Jim Crow era. Source: Jack Delano, May 1940, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

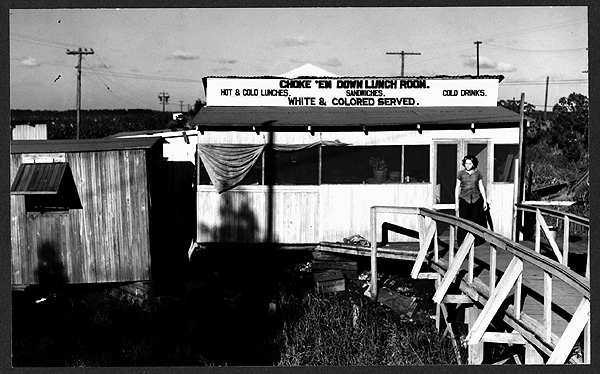

A lunch room for "White & Colored," Belle Glade, Florida, 1939.

This lunch room in Florida in 1939, assures service for both "White" and "Colored" at a time when many establishments refused service to African Americans. Source: Marion Post Wolcott, January 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

This lunch room in Florida in 1939, assures service for both "White" and "Colored" at a time when many establishments refused service to African Americans. Source: Marion Post Wolcott, January 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

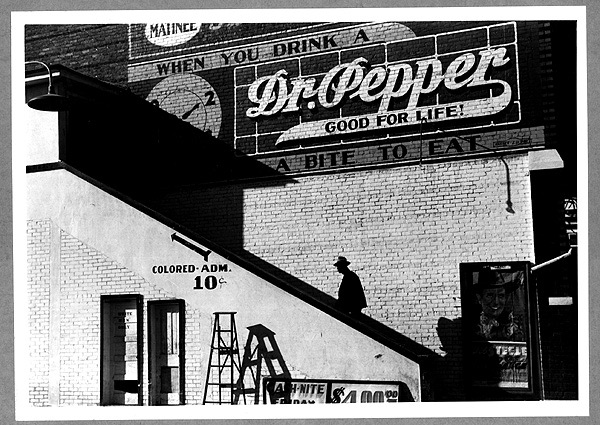

Negro man entering movie theater by "Colored entrance," Belzoni, Mississippi, 1939.

Black movie goers were directed to separate seating areas, usually in the balconies, of theaters, such as this one in Mississippi, in 1939. Source: Marion Post Wolcott, October 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Black movie goers were directed to separate seating areas, usually in the balconies, of theaters, such as this one in Mississippi, in 1939. Source: Marion Post Wolcott, October 1939, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 01

:

Jim Crow

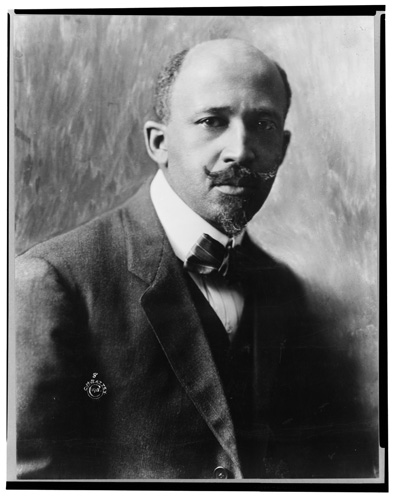

W.E.B. (William Edward Burghardt) Du Bois, 1868-1963.

Photograph of W.E.B. Du Bois, taken May 13, 1919. After calling upon African Americans to "close ranks" with the rest of the country during World War I, he declared to America, "Make Way for Democracy!" in 1919, as returning soldiers along with other blacks continued to suffer racial discrimination and attacks. Source: Cornelius M. Battery, May 31, 1919, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photograph of W.E.B. Du Bois, taken May 13, 1919. After calling upon African Americans to "close ranks" with the rest of the country during World War I, he declared to America, "Make Way for Democracy!" in 1919, as returning soldiers along with other blacks continued to suffer racial discrimination and attacks. Source: Cornelius M. Battery, May 31, 1919, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 02

:

The End of World War One

Lt. James Reese Europe.

Lt. James Reese Europe, who for four years was New York Society's favorite orchestra leader, served as regimental jazz band leader of the 369th Infantry, nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters. During their victory parade down Fifth Avenue in New York in 1919, the soldiers marched to the music of his band. Source: 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Lt. James Reese Europe, who for four years was New York Society's favorite orchestra leader, served as regimental jazz band leader of the 369th Infantry, nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters. During their victory parade down Fifth Avenue in New York in 1919, the soldiers marched to the music of his band. Source: 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Photo location:

SECTION 02

:

The End of World War One

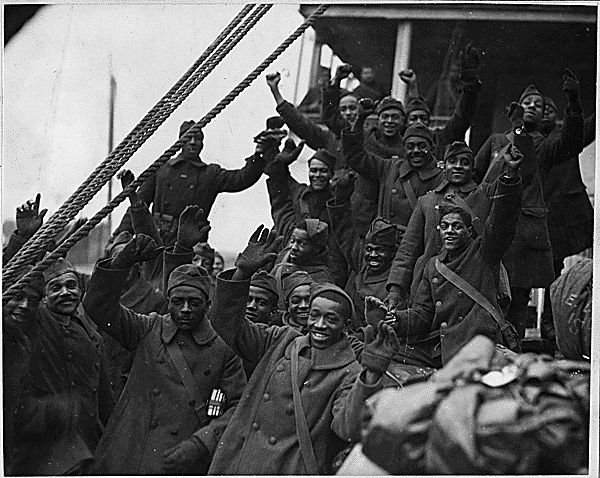

New York's famous 369th regiment arrives home from France, 1919.

Nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters, the 369th Regiment was the first all-black regiment to fight in World War I. They arrived in France in 1918 and fought on the front lines for six months, longer than any other American unit during the war. Source: ca. 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters, the 369th Regiment was the first all-black regiment to fight in World War I. They arrived in France in 1918 and fought on the front lines for six months, longer than any other American unit during the war. Source: ca. 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Photo location:

SECTION 02

:

The End of World War One

369th Regiment homecoming parade.

Children gathered along parade route celebrating the return of the 369th Regiment to New York, 1919. Upon their return from France, the members of the 369th Regiment were honored as heroes with a parade down Fifth Avenue in New York in 1919. Source: ca. 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Children gathered along parade route celebrating the return of the 369th Regiment to New York, 1919. Upon their return from France, the members of the 369th Regiment were honored as heroes with a parade down Fifth Avenue in New York in 1919. Source: ca. 1919, Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Photo location:

SECTION 02

:

The End of World War One

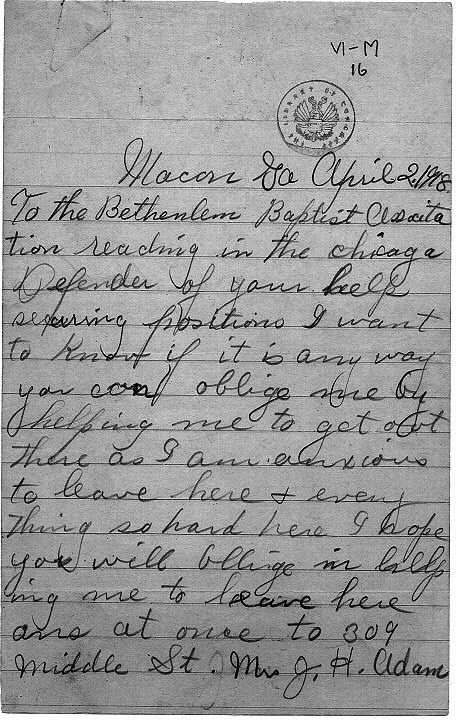

Letter from Mrs. J. H. Adams to the Bethlehem Baptist Association in Chicago, 1918.

Mrs. J. H. Adams was just one of the many black southerners who read of employment opportunities and other assistance available to new migrants to the north. Source: Carter G. Woodson Papers, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Mrs. J. H. Adams was just one of the many black southerners who read of employment opportunities and other assistance available to new migrants to the north. Source: Carter G. Woodson Papers, Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Photo location:

SECTION 03

:

The Great Migration

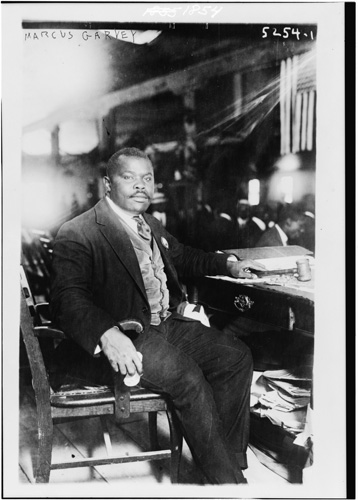

Marcus Garvey, August 5, 1924.

Photographed here on August 5, 1924, Marcus Garvey was the leader of the largest black mass movement in twentieth century America. Source: August 5, 1924, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photographed here on August 5, 1924, Marcus Garvey was the leader of the largest black mass movement in twentieth century America. Source: August 5, 1924, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 04

:

Marcus Garvey

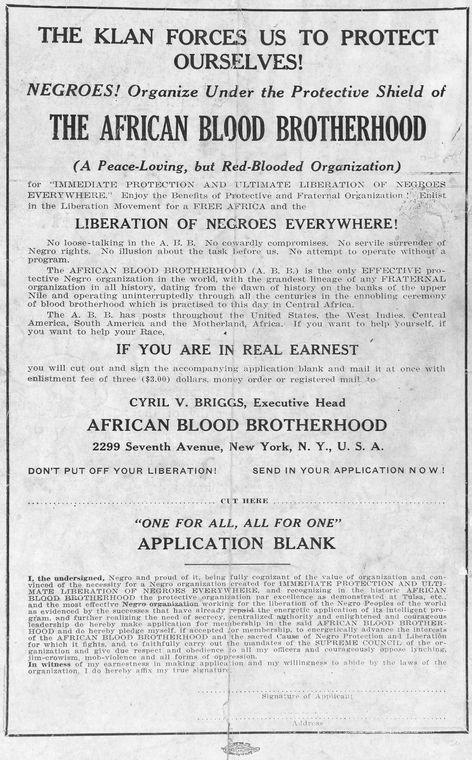

African Blood Brotherhood membership application.

The African Blood Brotherhood advertisement and membership application, published in the The Crusader, 1918-1922. Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture / Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division.

The African Blood Brotherhood advertisement and membership application, published in the The Crusader, 1918-1922. Source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture / Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division.

Photo location:

SECTION 05

:

Early Labor Movement

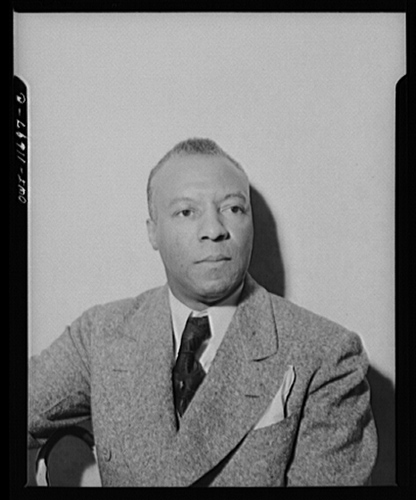

A. Philip Randolph, ca. 1935-1945.

Photographed here sometime between 1935 and 1945, A. Philip Randolph was an avid proponent of organized labor, advocating civil rights and economic justice. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photographed here sometime between 1935 and 1945, A. Philip Randolph was an avid proponent of organized labor, advocating civil rights and economic justice. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 05

:

Early Labor Movement

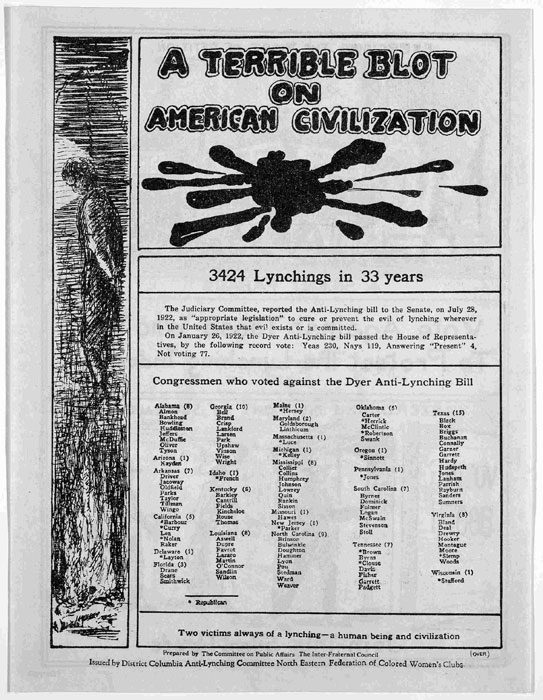

Flyer advocating the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, ca. 1922 (Slide 1).

In 1918, Congressman Senator Leonidas Dyer introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to Congress, which passed the House of Representatives in 1922, but failed to win passage from the Senate. This flyer, published by the DC Anti-Lynching Committee of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, called for the passage of the bill and identified those representatives who did not vote for the measure. Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

In 1918, Congressman Senator Leonidas Dyer introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to Congress, which passed the House of Representatives in 1922, but failed to win passage from the Senate. This flyer, published by the DC Anti-Lynching Committee of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, called for the passage of the bill and identified those representatives who did not vote for the measure. Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 06

:

Racial Violence and Terror

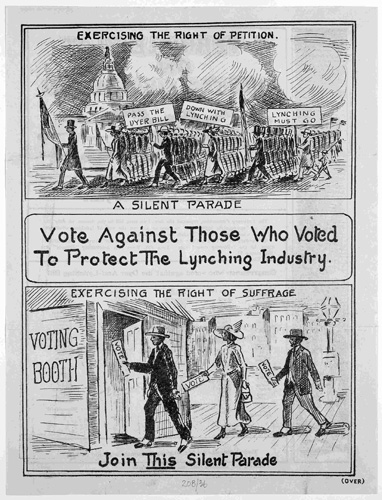

Flyer advocating the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, ca. 1922 (Slide 2).

In 1918, Congressman Senator Leonidas Dyer introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to Congress, which passed the House of Representatives in 1922, but failed to win passage from the Senate. This flyer, published by the DC Anti-Lynching Committee of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, called for the passage of the bill and identified those representatives who did not vote for the measure. Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

In 1918, Congressman Senator Leonidas Dyer introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to Congress, which passed the House of Representatives in 1922, but failed to win passage from the Senate. This flyer, published by the DC Anti-Lynching Committee of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, called for the passage of the bill and identified those representatives who did not vote for the measure. Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 06

:

Racial Violence and Terror

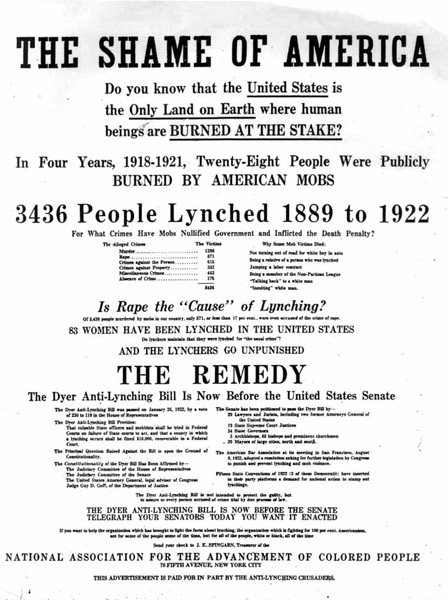

"The Shame of America" NAACP ad in support of Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, November 1922.

In November 1922, the NAACP ran this ad in the New York Times and other newspapers advocating for the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. Source: New York Times, November 23, 1922. Reprinted at http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6786. Last accessed December 5, 2008.

In November 1922, the NAACP ran this ad in the New York Times and other newspapers advocating for the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill. Source: New York Times, November 23, 1922. Reprinted at http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6786. Last accessed December 5, 2008.

Photo location:

SECTION 06

:

Racial Violence and Terror

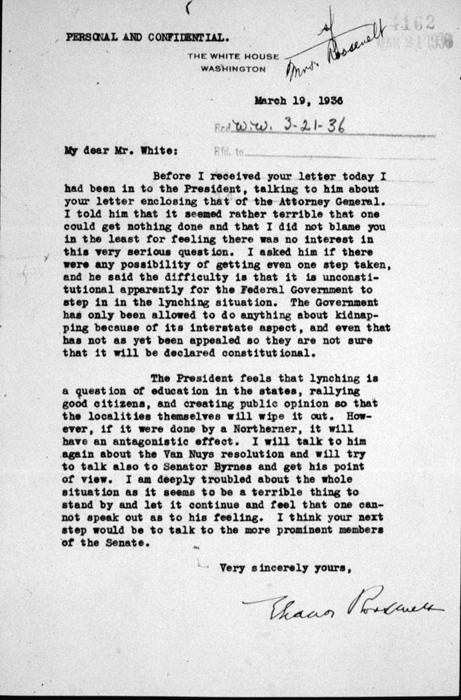

Eleanor Roosevelt's letter to NAACP's Walter White on lobbying against lynchings, March 19, 1936.

In this letter to the NAACP's Walter White, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt detailed some of her efforts to lobby the President on behalf of the anti-lynching cause. Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, DC.

In this letter to the NAACP's Walter White, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt detailed some of her efforts to lobby the President on behalf of the anti-lynching cause. Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 06

:

Racial Violence and Terror

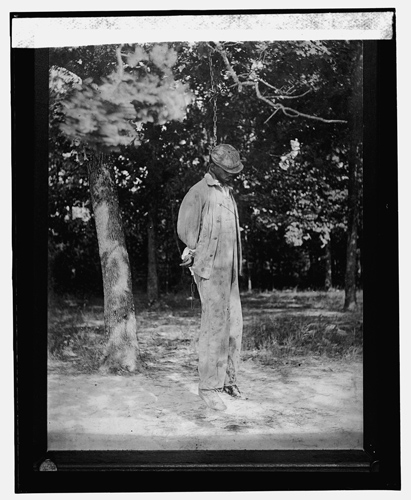

Lynching victim, 1925.

Between 1800 and 1951, at least 3,437 black people were lynched in acts of vigilante terror that targeted black men often falsely accused of sexual violence against white women. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Between 1800 and 1951, at least 3,437 black people were lynched in acts of vigilante terror that targeted black men often falsely accused of sexual violence against white women. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 06

:

Racial Violence and Terror

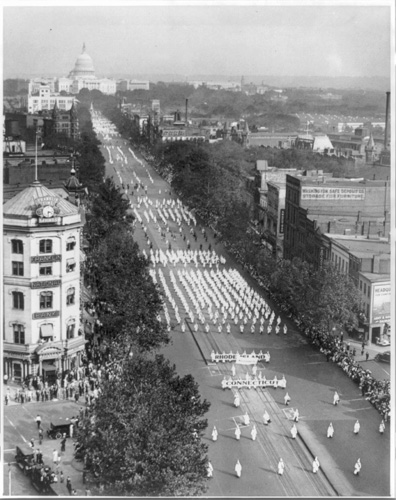

Ku Klux Klan parade (1926).

Ku Klux Klan parade Washington, D.C., on Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, September 13, 1926. While the original Ku Klux Klan declined in the 1880s, white racists reestablished the vigilante organization in 1915, seeking to capitalize on class anxieties about jobs and status. By the early 1920s, the Klan claimed between two and three million members, and controlled hundreds of elected officials and several state legislatures, not only in the South. The group's parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC highlighted the Klan's strength and boldness. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Ku Klux Klan parade Washington, D.C., on Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, September 13, 1926. While the original Ku Klux Klan declined in the 1880s, white racists reestablished the vigilante organization in 1915, seeking to capitalize on class anxieties about jobs and status. By the early 1920s, the Klan claimed between two and three million members, and controlled hundreds of elected officials and several state legislatures, not only in the South. The group's parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC highlighted the Klan's strength and boldness. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 06

:

Racial Violence and Terror

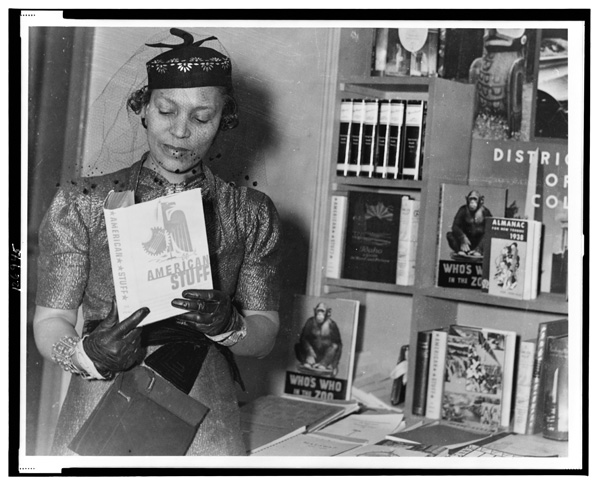

Zora Neale Hurston.

Zora Neale Hurston, at New York Times Book Fair, November 1937. Zora Neale Hurston was one among many poets, novelists, and writers who were part of the Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African American arts and letters. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Zora Neale Hurston, at New York Times Book Fair, November 1937. Zora Neale Hurston was one among many poets, novelists, and writers who were part of the Harlem Renaissance, a flourishing of African American arts and letters. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 07

:

Harlem Renaissance

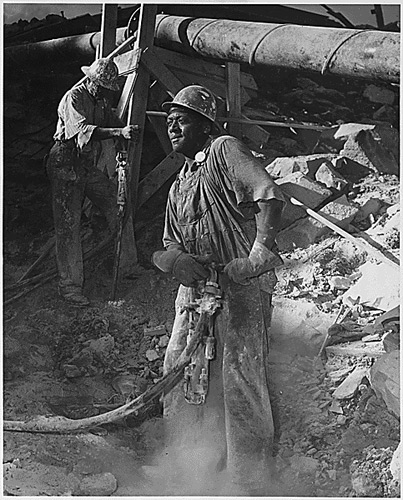

Black jackhammer operator at the Tennessee Valley Authority, June 1942.

During the Great Depression, African Americans were especially hit hard with high unemployment rates. Some found relief however through the Roosevelt administration's "new deal". Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.

During the Great Depression, African Americans were especially hit hard with high unemployment rates. Some found relief however through the Roosevelt administration's "new deal". Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.

Photo location:

SECTION 08

:

The Great Depression

Federal Emergency Relief Administration camp July 1934.

A Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) camp for unemployed Black women in Atlanta, GA. July 1934. Under President Roosevelt, the federal government created several agencies to assist those hit hardest by the Great Depression. Pictured here is a camp for unemployed black women in Atlanta. Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.

A Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) camp for unemployed Black women in Atlanta, GA. July 1934. Under President Roosevelt, the federal government created several agencies to assist those hit hardest by the Great Depression. Pictured here is a camp for unemployed black women in Atlanta. Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.

Photo location:

SECTION 08

:

The Great Depression

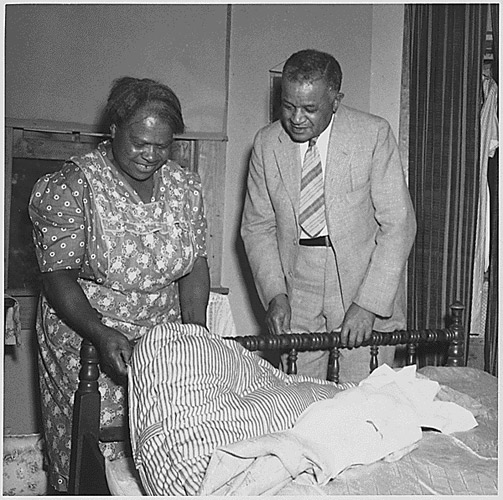

Surplus cotton mattress.

Just one of the million mattresses made by low-income farm families, 1942. Shown here, a Maryland woman shows her mattress to a Federal field agent. Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.

Just one of the million mattresses made by low-income farm families, 1942. Shown here, a Maryland woman shows her mattress to a Federal field agent. Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, Hyde Park, New York.

Photo location:

SECTION 08

:

The Great Depression

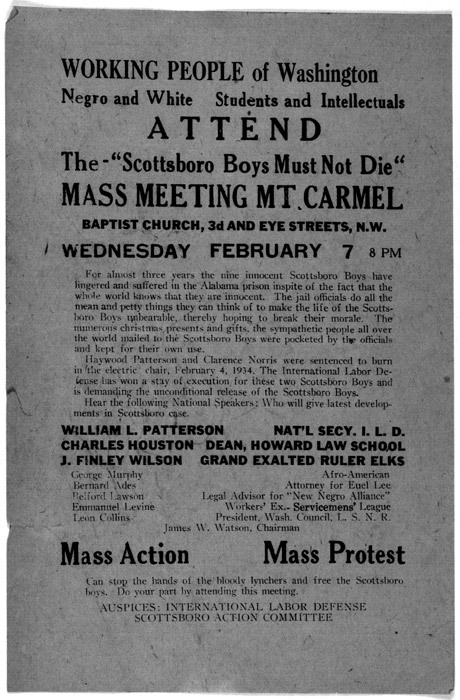

Flyer for organizing meeting to protest the Scottsboro boys' conviction (February 7, 1934).

A flyer announcing a "Scottsboro boys must not die" mass meeting, organized by the International Labor Defense Scottsboro Action Committee. Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

A flyer announcing a "Scottsboro boys must not die" mass meeting, organized by the International Labor Defense Scottsboro Action Committee. Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 09

:

The Scottsboro Trial

United We Win [World War II Poster] (1943)

In an effort to counter the demoralizing effect of racial segregation and discrimination, the U.S. government launched several campaigns that highlighted the contributions of African Americans to the war effort. Source: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

In an effort to counter the demoralizing effect of racial segregation and discrimination, the U.S. government launched several campaigns that highlighted the contributions of African Americans to the war effort. Source: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Photo location:

SECTION 10

:

End of World War Two

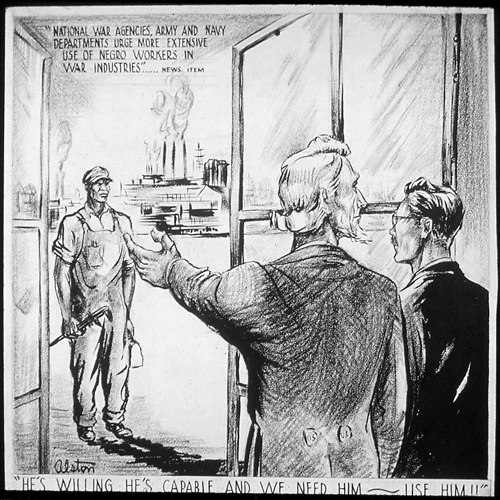

"He's Willing, He's Capable, and We Need Him - Use Him!" (1943).

This cartoon encourages defense industry employers to hire African American workers. Source: Office of War Information, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

This cartoon encourages defense industry employers to hire African American workers. Source: Office of War Information, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Photo location:

SECTION 10

:

End of World War Two

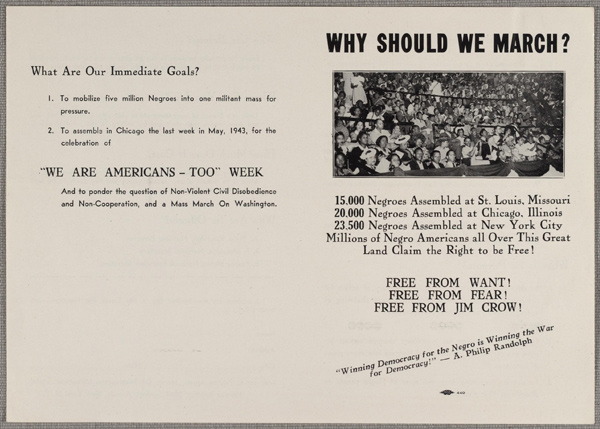

Flyer for March on Washington Movement, 1941 (Slide 1).

In 1941, civil rights activist and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in defense industries. Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C.

In 1941, civil rights activist and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in defense industries. Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C.

Photo location:

SECTION 10

:

End of World War Two

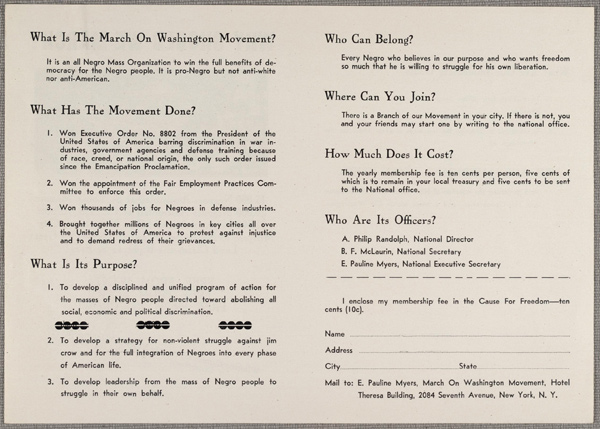

Flyer for March on Washington Movement, 1941 (Slide 2).

In 1941, civil rights activist and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in defense industries. Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C.

In 1941, civil rights activist and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph threatened to organize a march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in defense industries. Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C.

Photo location:

SECTION 10

:

End of World War Two

Colonel Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. and Edward Gleed of the Tuskegee Airmen, March 1945.

During World War II, in response to civil rights activists call for equal treatment of black soldiers, the government provided training for black pilots in a segregated base located in Tuskegee, Alabama. The 99th Pursuit Squadron, an all-black fighter unit known as the Tuskegee Airmen received its training here and would go on to fight with distinction performing bomber-escort, dive-bombing, and strafing missions in Europe. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

During World War II, in response to civil rights activists call for equal treatment of black soldiers, the government provided training for black pilots in a segregated base located in Tuskegee, Alabama. The 99th Pursuit Squadron, an all-black fighter unit known as the Tuskegee Airmen received its training here and would go on to fight with distinction performing bomber-escort, dive-bombing, and strafing missions in Europe. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Photo location:

SECTION 10

:

End of World War Two

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr.

Harlem minister and political activist Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. organized boycotts, rallies, and protests against discrimination in hiring practices, wages, and working conditions. In 1944, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives--the first black Congressman from New York, and the second in the country. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Harlem minister and political activist Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. organized boycotts, rallies, and protests against discrimination in hiring practices, wages, and working conditions. In 1944, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives--the first black Congressman from New York, and the second in the country. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Photo location:

SECTION 11

:

Voting Rights

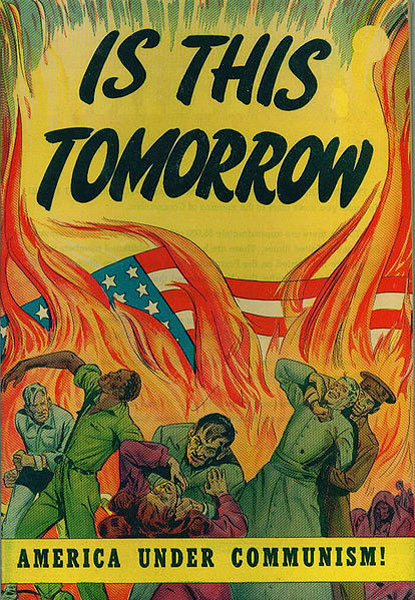

Cover to the propaganda comic book “Is This Tomorrow”.

Source: Catechetical Guild.

Source: Catechetical Guild.

Photo location:

SECTION 12

:

McCarthyism

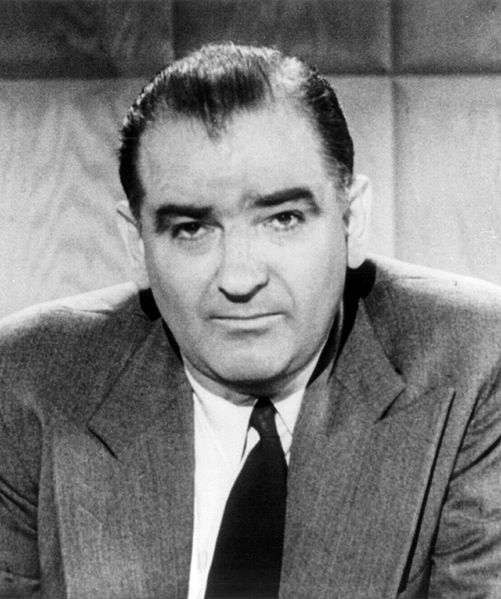

Joseph Raymond McCarthy, 1954.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC. [LC-USZ62-71719].

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC. [LC-USZ62-71719].

Photo location:

SECTION 12

:

McCarthyism

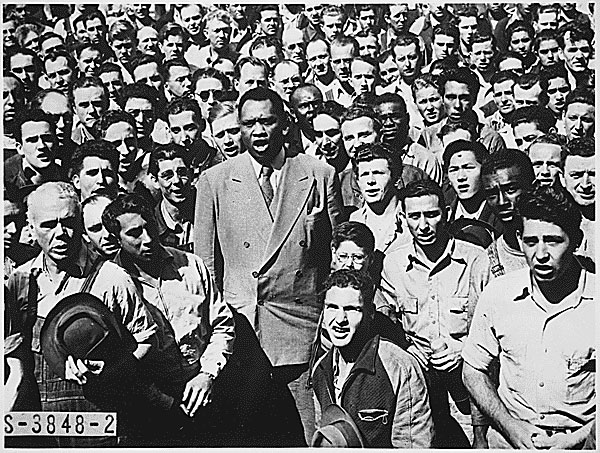

Paul Robeson leading shipyard workers in singing the Star-Spangled Banner, September 1942.

Paul Robeson, world famous baritone, leading Moore Shipyard [Oakland, CA] workers in singing the Star Spangled Banner, here at their lunch hour recently, after he told them: "This is a serious job---winning this war against fascists. We have to be together." Robeson himself was a shipyard worker in World War I. Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Paul Robeson, world famous baritone, leading Moore Shipyard [Oakland, CA] workers in singing the Star Spangled Banner, here at their lunch hour recently, after he told them: "This is a serious job---winning this war against fascists. We have to be together." Robeson himself was a shipyard worker in World War I. Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Photo location:

SECTION 13

:

Pop-Culture

Marian Anderson performance at the Lincoln Memorial.

Singer Marian Anderson performing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, April 10, 1939. After the Daughters of the American Revolution denied Marian Anderson permission to perform before an integrated audience at the DAR Constitution Hall, the Roosevelt administration intervened and staged her performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The critically-acclaimed concert was attended by over 75,000 people. Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Singer Marian Anderson performing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, April 10, 1939. After the Daughters of the American Revolution denied Marian Anderson permission to perform before an integrated audience at the DAR Constitution Hall, the Roosevelt administration intervened and staged her performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The critically-acclaimed concert was attended by over 75,000 people. Source: Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S), National Archives at College Park, MD.

Photo location:

SECTION 13

:

Pop-Culture

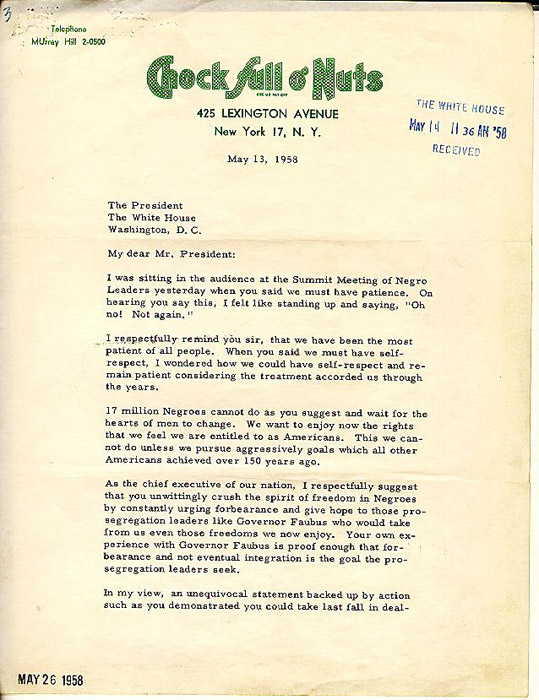

Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower (Slide 1).

Jackie Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower urging more aggressive civil rights protections, May 13, 1958. Source: White House Central Files, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abiline, KS.

Jackie Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower urging more aggressive civil rights protections, May 13, 1958. Source: White House Central Files, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abiline, KS.

Photo location:

SECTION 13

:

Pop-Culture

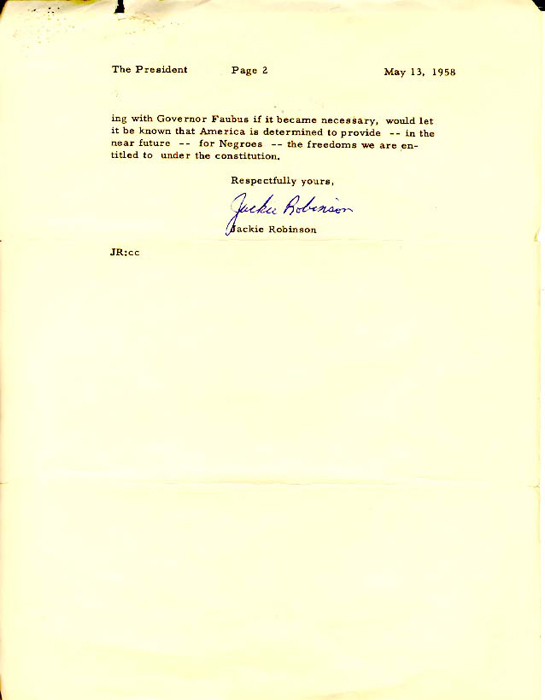

Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower (Slide 2).

Jackie Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower urging more aggressive civil rights protections, May 13, 1958. Source: White House Central Files, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abiline, KS.

Jackie Robinson's letter to President Eisenhower urging more aggressive civil rights protections, May 13, 1958. Source: White House Central Files, Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abiline, KS.

Photo location:

SECTION 13

:

Pop-Culture

![United We Win [World War II Poster] (1943)](/assets_c/2009/06/image_07_10_010_united-thumb-360x470-823.jpg)